No. 271: GENE TUNNEY / Ever erudite & hopelessly vain, he claimed he won the heavyweight championship of the world thanks to a lowly scribe's insight. Fact-checking a century later.

I've never bought the idea that sportswriters wield any influence, tho' many imagine it so. They'd revel in Tunney's tale of a humble scribe's role in boxing's great upset. Entirely bogus, of course.

In my trade, I’m dedicated to the truth, in particular about my profession. If people ever say something nice about a sportswriter, well, they better be able to back it up. I won’t relent in my search for the verifiable truth.

I have in the past mentioned Gene Tunney, not in a flattering way. Check out this entry, No. 163: MUHAMMAD ALI, ROCKY MARCIANO, THE HISTORIAN & THE NCR 315 / Chasing the story about the dawn of computer sports and bargaining with the boxing's esteemed hoarder. (You’ll need at least a trial subscription to access it.)

No. 163, the story about my fraught and ultimately failed negotiations with ring archivist Hank Kaplan, was the gist of a chapter in my Audible memoir. (The chapter’s title was “Don’t Seem Needy & Risk Over-Selling Your Story.” I hope I’m not seeming needy here.)

Tunney makes a cameo in the text—he was the only living heavyweight champ in the tournament field who balked at giving his blessing to a boxing fantasy tournament, a weekly radio broadcast that transfixed me as a kid.

I dunno. Maybe Gene Tunney gave good glower, but he didn’t exactly cut a figure like Ali and Tyson.

The tournament which crowned Marciano as champion was a byproduct in equal parts of Mr Kaplan’s research and a primitive computer’s imagination. Joe Louis, Jack Dempsey, Ali and Marciano gave interviews on air and likewise less famous others who had their palms greased by the promoter … but Tunney didn’t play along, couldn’t be bought. Yeah, out of all the old-timers, Tunney was the lone stick in the mud.1

In No. 163 and in the Audible memoir, I tell the story of Rocky Marciano shedding 40 pounds, donning a toupee and getting back into the ring with a full decade after his retirement to fight with Muhammad Ali … or at least stage a “fight” which was choreographed by a computer. I watched on closed circuit, as did hundreds of thousands of boxing-loving marks around the world.

You might consider it weird that I much worry about a heavyweight champion from a century ago—factor in my age, though, and he becomes a less remote figure. I was born not even three decades after his last fight. In my youth, into my high-school days, he was what they’d call a living legend, they being the hackiest of hacks.

I was a boyhood student of fisticana and I recall leafing through Ring magazines at the barber shop. I remember distinctly editor Nat Fleischer’s rankings of the 10 greatest heavyweight champions of all time, which landed in an issue when I was in Grade 6—in order, Jack Johnson, Jim Jefferies, Bob Fitzsimmons, Jack Dempsey, Jim Corbett, Joe Louis, Sam Langford, Gene Tunney, Max Schmeling, Rocky Marciano.

The octogenarian Fleischer—somehow, he seemed even older—was getting his affairs in order back in 1968 and this matter of the greatest of all time was among his career priorities. No small point of controversy in his rankings, mind you. No Cassius Clay, as Fleischer and the Ring stubbornly called him though he had changed his name. No Sonny Liston, largely shunned by the magazine because of his criminal connections. No Joe Frazier, because he was only emerging at that point. Many laughed off Fleischer’s rankings, though, he brought some expertise to the package, having actually been in attendance at their fights—yup from Gentleman Jim Corbett and Ruby Bob Fitzsimmons at the turn of the century through to Ali in his prime. (In fact ol’ Nat had been sitting ringside next to the timekeeper at the Ali-Liston fight in Lewiston, Maine, and his alerting of celebrity referee Jersey Joe Walcott to the timekeeper’s count of the knockdown muddled affairs in the ring, contributing to the mayhem.)

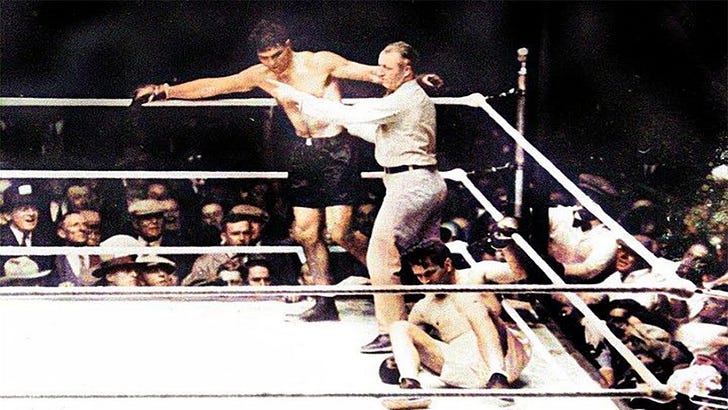

Curiosities abounded at every slot in Fleischer’s rankings (e.g., Nova Scotia’s Sam Langford never even got a title shot back in his day), but none bothered me more than the inclusion and elevation of Gene Tunney, who won the championship from Jack Dempsey back in 1926, won a rematch in ‘27 and defended his title for a second and last time the year after that. Yeah, Tunney lost only one fight over his professional career, to Harry Greb, the Pittsburgh Windmill being one of the all-time greats in the middleweight and light heavyweight divisions; and Tunney avenged that loss thrice and also fought Greb to draw. His record of 81-1-3, 48 knockouts, is impressive enough … but I never liked him. Yeah, it was grainy old fight film footage, like the YouTube video at the top of this SubStack entry, but it was all I needed to see.

Some of it is a matter of style. Dempsey was a more colourful figure, whereas Tunney was clinical. Dempsey’s nickname was the “Manassa Mauler,” evocative and as such truth in advertising. Tunney was billed as “the Fighting Marine,” a shrewd bit of marketing, given some hard feelings about Dempsey avoid the service; fact was, Tunney had enlisted but upon discharge seemed little inclined to go to war in the ring, preferring chess matches to life-or-death combat.

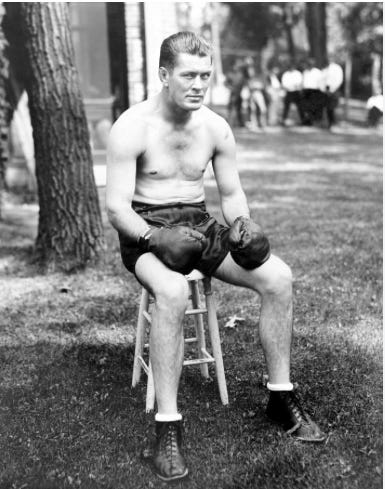

This isn’t an extra in the cast of The Great Gatsby—it’s Gene Tunney looking none the worse for wear and completely at home in one of his tuxedoes in a photo dated prior to his wins over Jack Dempsey.

You can reasonably wonder why all this irks me, but fact is, growing up I had heard of Tunneys in the U.S. who were related by marriage to our strain of Joyces and I was sold a bill of goods that the most famous Tunney was among them. I had also heard stories of Gene Tunney’s near-infinite wealth: that he had saved pretty much every red cent he earned in the ring, including $990,000 for each of the Dempsey fights; that he had married an heiress to the Carnegie fortune; that he had befriended J. Paul Getty, who back in the 60s was the world’s richest individual and gave the ex-champ investment advice. Hearing all this one thought furrowed my young brow: Did J. Paul Getty tell him not to share it with his extended family?

Well, later in life, I did a cursory search and nothing pointed to any link between our Joyces and his Tunneys. A family fish tale. I did find out, however, that we were related to the second most famous Tunney, actress Robin Tunney (Prison Break, The Mentalist and, sigh, Encino Man).2

The Facebook post after my daughter’s 23andMe results came in and verified the family connection.

I read up on the life stories of all the heavyweight champs as a kid, but reserved a special interest for a few and I read about Gene Tunney more than most. His arc was Horatio Alger stuff—though he looks in the photo above like he was to the manor born, by all accounts he grew up hardscrabble in New York, his parents from County Mayo and his father an unpleasant and abusive sort indigenous to the Auld Sod. (Only by birthright I can say that, so spare me accusations of hibernophobia.) Dickens’s starving orphans would have considered young Gene cruelly hard done by.

Though he looks in the photo like a college man, he had no shot at higher education given his lowly birth and its bad timing, what with World War I. Nonetheless, Tunney was a voracious reader and an autodidact—yeah, he compensated in that way only those denied a fair shake can. Yup, he lectured on Shakespeare at Yale, and yup, he hung out with George Bernard Shaw, and yup, he even played a role in the creation of the CIA, as laid out in brief in this video below. Gene Tunney was a complicated guy who had first become rich and famous in the most uncomplicated way.

Jim Murray, the Los Angeles columnist and an object of worship among the scribes, wrote this bit of hagiography of Tunney after his death (and it pains me to read it):

Tunney was unloved, underrated, shunned by his own people, rejected by history. Still, he was the best advertisement his sport has ever had. … He was like no Irishman you ever saw, but he was the greatest Irish athlete who ever lived.

Well, he was unloved by me.

Now, Tunney wasn’t quite as smart as he thought. He might have made a lot of good calls about his investments, though the Rumble in the Jungle wouldn’t have been one of them. His prediction in the New York Daily News prior to the Muhammad Ali-George Foreman fight:

‘Foreman will knock him out in two rounds. Dempsey would have done it in one round. A lot of the old champions could have beaten this fellow Ali. Harry Greb would have made a fool out of him. He was the best boxer-puncher of them all. I believe I could have beaten Ali. I was smarter and I think I punched a little harder than Ali does. I’m not saying all of the former champions were better than today’s modern champions …

To my ear, that sounds like he’s saying that exactly and in spades, alone as they say in euchre. In this case, he’d have been properly euchred,

Not so long after Ali beat Foreman, I was out of school and working at the Coca-Cola bottling plant when I picked up a copy of Press Box: Red Smith’s Favorite Sports Stories. Yeah, here is my copy 49 years after the fact.

For this wannabe scribe, Press Box wasn’t exactly the bible, not in the way that The Red Smith Reader would later be and some other anthologies of classics from newspapers and rags. This wasn’t a round-up of the columnist’s own work from the New York Times, but rather an eclectic assortment of stuff to the great man’s tastes, yarns that either touched or tickled him: Jimmy Breslin on Stengel, Throneberry and rest of the ‘62 Mets; John McPhee on Bill Bradley’s last game at Princeton; John Updike on Ted Williams’s last at-bat at Fenway. Red’s best friend W.C. Heinz is in there, ditto John Lardner and Grantland Rice. Unique among the names, though, is Gene Tunney.

He’s not just the subject of a piece, but also its author. Not a ghost-written deal either.

For those of you playing along at home, the guy wins the heavyweight title, makes millions, gets the debutante, hangs out with famous folks, serves his country … and then lives my dream in his spare time.

I was properly aghast, but it only got worse when I read it.

Yes, Tunney wrote one of Red Smith’s favourite sports stories, one that appeared in, of all places, Field and Stream, according to the acknowledgments.

Not that “The Long Count” wasn’t well-written. (Remind me to pick up Field and Stream, will you?)

Maybe my opinion is coloured by my animus, but I feel it’s a tad over-written. And he takes his own sweet time getting there, 5,000 words in all—this isn’t Tunney’s full autobiography including friendships with Getty and J. Edgar Hoover and various American five-star generals, but solely his account of his two fights with Jack Dempsey. You know Dempsey, the guy who woulda kayoed Ali in one round per Tunney. Sigh.

I’ve reprinted the entire story below the paywall at the foot of this SubStack entry, yours to peruse (though it would take a real diehard and boxing fan to finish it), but I’m going to dwell here at the top of the story.

Tunney says his confidence in his ability to beat the great Dempsey was founded on advice given to him during his military service from an enlisted man, Corporal McReynolds (no first name), who during peacetime had been a sportswriter in Joplin, Missouri—as Tunney describes him, “one of those Midwestern newspapermen who combined talent with a copious assortment of knowledge [and possessed] a consummate understanding of boxing,”

From as much as I can tell, Tunney wasn’t a fan of scribes during his brief reign as champion and in his more serious and consequential later life. They were beneath him—common sorts of the ilk that he had escaped through his character and genius, Precisely why he’d be taking the advice of sportswriter and, no offence to the Show-Me State, one from Joplin, Missouri, is utterly beyond me. It just doesn’t fit.

I call BLARNEY!

Through the miracle of newspapers.com, the most worthwhile database, I went back 110 years to Joplin’s newspapers. Yes, there was a newspaperman by that name, one Edward Harlan McReynolds, and it seems he dined out on his connection with Gene Tunney for many years. Okay, so far so good.

In Tunney’s telling, however, McReynolds told Tunney that a slick technician could beat Dempsey the same way the skilled Mike Gibbons beat Jack Dillon, a fighter in Dempsey’s template. All paper covers rock, all scissors cutting paper. Further, Tunney writers that McReynolds eye-witnessed the Gibbons win over Dillon. From “The Long Count”:

“Yes,” the Corporal replied. “I saw that bout. Gibbons was too good a boxer. He was too fast. His defence was too good. Dillon couldn't lay a glove on him.”

To this I can only say, bovine feces.

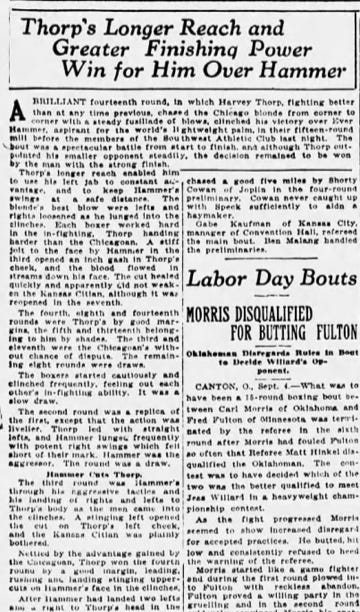

The paper that McReynolds worked for was the Joplin Globe. The Globe isn’t in the database, but the other Joplin paper of the day, the News Herald is. This is what ran in the Joplin N-H after Gibbons’s win over Dillon. The reproduction here is a little blurry, but you can see that the bout was in Terre Haute, Indiana, and it gets a single paragraph and second billing.

Gibbons’s W over Dillon gets second billing—hard to see why it would rate over Hall of Famers Benny Leonard, an all-timer at 135, even if it was a non-title fight in Toronto.

Even if the Tribune had significantly more resources than the Globe, I can’t imagine that the paper would have sent McReyonolds out of state, 451 miles, to carry an account of a fight that wasn’t the biggest of the day ,,, on a holiday weekend. Not when a story from a wire service or syndicated scribe would have been available.

And if the Globe had dispatched a staffer, it wouldn’t have been McReynolds. This from a tribute page to Edward McReynolds put together by his family (linked here):

During World War I, Edward and Augusta lived in Joplin, MO, where he worked as a telegraph editor for the Joplin Globe newspaper. Their home was at 919 Jackson Avenue. When registering for the military draft, in June 1917, he was described as tall and of medium build, with light brown eyes and dark brown hair.

As a journalist, Edward undoubtedly covered the business of the railroads which were such a significant part of the Kansas City and Northwest Missouri economy at the time. Among these would have been the Missouri Pacific Railroad ("Mo-Pac"), and his abilities as a writer must have caught the attention of top railroad officials, such as Missouri Pacific president Lewis W. Baldwin. The Mo-Pac was based in St. Louis with a major operation in Houston, TX.

No, Tunney was surely fudging here or McReynolds was fudging or, I suspect, both. Tunney knew McReynolds from the service. No doubt boxing would have been an interest to the newspaperman. I don’t doubt that he would have seen Dempsey fight (at least on newsreel film). I’m sure he knew the names of Gibbons and Dillon—they would have come over the telegraph. He might have had the misfortune of working that Labor Day weekend—if he had, he’d have been working a big local fight that received a lot of attention in the paper that day: a big win for Harvey Thorp, who fought out of Joplin and parts nearby.

Yeah, McReynolds wouldn’t have left Joplin that day, but Tunney had a story to tell. What could be more unbelievable than a sportswriter actually having an insight, never mind one that gave a vet hope and in just a few years making him a millionaire? Apologies to Jim Murray here, but on this count Tunney was like ever other Irishman you ever saw—he wouldn’t let the truth get in the way of a good story.

No one would buy “The Long Count” if you sold it as fiction, what with scribes’ sorry reputation, but it was Tunney’s story and he ran with it. Enjoy it for what it is.

THE LONG COUNT

by Gene Tunney from Press Box

THE laugh of the Twenties was my confident insistence that I would defeat Jack Dempsey for the heavyweight championship of the world. To the boxing public, this optimistic belief was the funniest of jokes. To me, it was a reasonable statement of calculated probability, an opinion based on prize-ring logic.

The logic went back to a day in 1919, to a boat trip down the Rhine River. After the First World War, the army sent a group of AEF athletes to the German Rhineland to give exhibitions for doughboys in the American occupation forces. I was the light heavyweight champion of the AEF. Sailing past castles on the Rhine, I was talking with the corporal in charge of the party. Corporal McReynolds was a peacetime sportswriter in Joplin, Missouri, one of those Midwestern newspapermen who combined talent with a copious assortment of knowledge. He had a consummate understanding of boxing, and I was asking him a question of wide interest in the AEF of those days.

We had been hearing about a new prize-fighting phenomenon in the United States, a battler are burning up the ring back home. He was to meet Jess Willard for the heavyweight championship. His name was Jack Dempsey. None of us knew anything about him, his rise to the challenging position for the title had been so swift. What about him? What was he like? American soldiers were all interested in prize-fighting, I more so than most--and AEF boxer with some idea of continuing my ring career in civilian life.

The corporal said yes, he knew Jack Dempsey. He had seen Dempsey box a number of times, and had covered the boats for his Midwestern paper.

“Is he good?” I inquired.

“He's tops,” responded Corporal McReynolds. “He'll murder Willard.”

“What's he like?” I asked.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.