No. 245: DICK ALLEN & LARRY MERCHANT / When race-baiting around the Phillies' batting cage boiled over & an old pro's view from the press box in Philly back in '65.

Allen was elected to the Hall of Fame this week. What might have been if he had tapped his potential? How a fight made a villain out of an emerging star. How it might have soured him on the game.

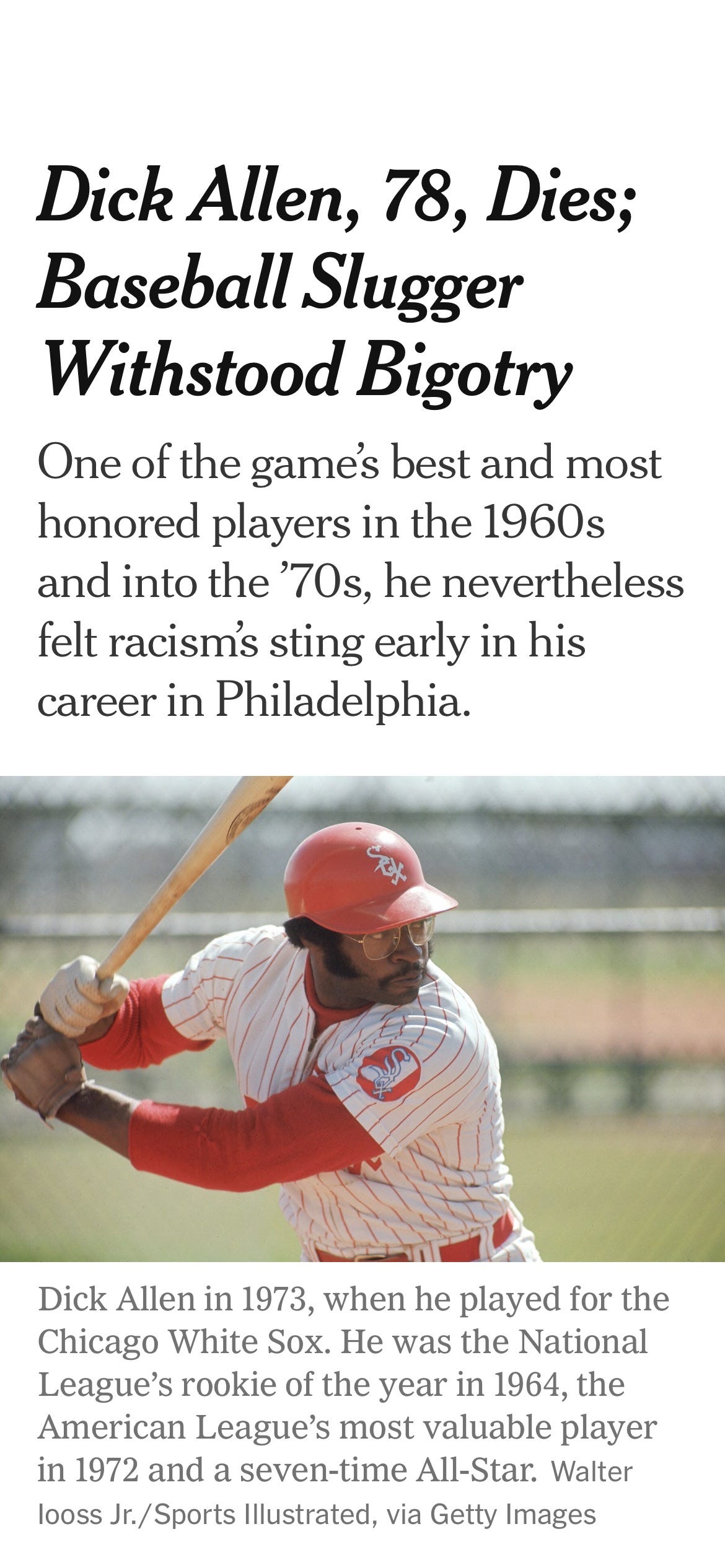

The featured photo and display for my Sportsnet.ca story about the Hall of Fame passing over Dick Allen eight years ago.

I couldn’t be the only fan of my vintage happy to see Dick Allen elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame the other day. Posthumously elected, alas, Allen having died in 2020. The question always hangs there: Couldn’t you have done this while he would have been around to enjoy his moment? Another in this particular case: Grim mortality aside, how is his candidacy substantially different in 2024 than it was a decade ago, when his name was kicked around?

Selfishly, I wish he lived long enough to make it to the induction ceremony, because I’m intrigued by what he would say at the podium on his big day—after all, with this vote by the Classic Baseball Era Committee, the MLB establishment seemed more accepting of him than it had been back when he was a young phenom or even when he was the most dangerous hitter in the game. He lived a life, as they say--twists, turns, ups, downs, fury but what seemed like some sort of peace towards the end of his life. He was often misunderstood. Four years after his passing, he remains a curiosity, an enigma, if not a mystery.

Back in those days, Muhammad Ali made lyric poetry that captured his bravado. Allen got across his discontent in a single word he etched in dirt.

I tried reaching out to Allen in 2016 to discuss his life and times and, with it, his candidacy for the Hall of Fame. I thought I had a decent shot—one of Allen’s longtime friends was Mark (Frog) Carfagno, a former groundskeeper with the Phillies, put in the good word for me.

Mark mentioned that the proposed piece would be featured in a series of stories for Black History Month and that I wanted to dwell on the season he spent with Philadelphia’s affiliate in Little Rock, Arkansas, where the fan base didn’t bother to veil its racism. (Sample banner hung over the outfield wall: “Don’t Negro-ize baseball.”) In a package of stories to give Allen an idea of my work, I included a piece I wrote about Geese Ausbie, the coach of the Harlem Globetrotters, who had played college ball in Little Rock in the late 50s. Ausbie, who had been heir to Meadowlark Lemon’s title of the Clown Prince of basketball with the Globies, was as serious as heart surgery when talking about Little Rock during the fraught times of Brown vs the Board of Education.

Here, another ‘alas.’ Allen took a pass. Thanks, but no thanks. To my mind, the retrospective Dick Allen piece I filed for Sportsnet is decent enough—I’ll link it here. Larry Merchant though it was “a good overview.” I put it down as a nice try.

Not the only one who got away, but still … I had been a fan of Allen going back to his early days in Philadelphia, where he won the National League Rookie of the Year in 1964. Back at the start of his career, he went by Riche Allen. By the late 60s, when I started tracking MLB with the unworldly enthusiasm that only a middle-schooler can muster, Allen was always high on my list of players of interest.

I guess I should say, “a name of interest” because there was no way of seeing him play in those days, given that only baseball broadcasts available in Toronto were the NBC Game of the Week aired by the network’s Buffalo affiliate on Saturday afternoons and available in the Joyce living room in glorious black and white. (And pray it wouldn’t rain, or there’d be no baseball at all for the fortnight.) The Phillies were long-time tenants of the National League cellar, so they never landed on the network’s schedule. Not the remotest prospect of seeing them in the World Series.

I knew of Richie Allen (the name he went by in the 60s) only from newspaper accounts of his 500-foot home runs, from the occasional mentions of him in Sports Illustrated (the ‘Boo photo of course,), and from the All-Star Game. Back in those days, Allen played third base and in 1967 he was the NL’s starting third baseman in the mid-summer classic in Anaheim, which was still new enough to the American League to be a novelty. Famous names abounded that night, enough that baseball history achieved something akin to critical mass: Aaron, Clemente, Mantle and Mays, just to start, two dozen Hall of Famers in all, plus Pete Rose.

In that game Allen led off the second inning with a homer off Dean Chance. The AL tied it up in later innings and game went to 15 innings (30 K’s no less) before Tony Perez hit a HR off Catfish Hunter for the winning run. (Mixed blessing going 15 innings. Extras gave every opportunity to get all of the future Hall of Famer into the game. Sadly, though, the game extended well past the bedtime of any 11-year-old in the Eastern Time Zone.)

When Allen died, the New York Times worked his All-Star Game appearances (seven) into his obit, along with his career homers (351), his seasons batting .300 (seven official, not including an eighth when a broken leg cut short his season and left him short of qualifying at-bats) and, of course, his MVP in 1972. The matter of race, though, was up there in the headline and deck.

In that obit, the NYT’s Richard Goldstein pulled a couple of lines that Mike Schmidt, the Phillies’ HOF third baseman, offered at a ceremony in Philadelphia honouring Allen a few months before his death. “Dick was a sensitive Black man who refused to be treated as a second-class citizen,” Schmidt said. “He played in front of home fans that were the products of that racist era [and on a team with “racist teammates [with] different rules for whites and blacks.”

Schmidt went on: “Fans threw stuff at him and thus Dick wore a batting helmet throughout the whole game. They yelled degrading racial slurs. They dumped trash in his front yard at his home.”

A fitting sentiment, but—and I say these as an ever-hopeless fan of Mike Schmidt as a ballplayer and a man—these were second-hand retellings. Schmidt wasn’t around for Allen’s first go-round in Philly in the 60s. They were Phillies teammates when Allen came back to Philadelphia in 1975, at age 33, on the steep downslope of his career arc. Allen had gone from MVP status with the White Sox to replacement player in three seasons. What Schmidt knew of the Phillies in the 60s he had heard from Allen and others in and around the organization—doesn’t mean it’s not true, but maybe only true as far as it goes. Some relevant stuff might be omitted, and historic details might be enhanced.

(An aside: For my account of the suicide of the Phillies scout who signed Schmidt and Ferguson Jenkins among others, check out the link here, No. 89: TONY LUCADELLO / Wall of Dreams revisited which appeared on this SubStack on March 30, 2023. I heard second-hand that Schmidt had read the piece I wrote for ESPN in 2005 and looked seriously at developing it into a film, dramatic or documentary I never found out.)

The NYT also notes Allen’s “reputation as a difficult personality” in his time with the Phillies in the 60s, including a suspension for not showing up for a double-header and a fine for missing a flight. Really, though, the obit in its entirety feels like a once-over-lightly treatment of a former major-leaguer—I’m banking the section’s editors would have carved out more space and bandwidth for a former player already honoured in Cooperstown, if he had been a Yankee or Dodger.

No mention is made of the catalyst for that “reputation as a difficult personality”: a fight in batting practice with a Phillies team-mate Frank Thomas on July 3, 1965, a contretemps that prompted the Phillies to release Thomas the next day. The matter was discussed somewhat this week when the Classic Era Committee did what should have been done earlier with its election of Allen to the Hall of Fame.

Still, what happened in that fight … well, it’s hard to trust accounts have been told and retold and passed on across the generations. So, I decided to go back and: 1. dig up contemporaneous accounts in the Philadelphia newspapers; and 2. talk to someone who was there, someone who as a reporter tracked Allen in that stint with the Phillies in the 60s. The former was easy with a pass to a vast newspaper archive—it’s easier to get the Inquirer and the Daily News from 1965 than yesterday’s edition. The latter, though, might be slightly harder—thankfully, I have the home number of Larry Merchant, who was a columnist with the Philadelphia Daily News in Philadelphia back in the 60s, before he landed at the New York Post and HBO, where he became the standard that all boxing analysts are measured against. Larry is 93, steaming towards 94. The World Series that is his life has gone to Game 7 and is well into extra innings. I don’t know if he has more than a decade or two left, but the fact is he’s ridiculously sharp and he agreed to a chat which you’ll find as an audio below the paywall for paid subscribers.

FIRST, the fight with Frank Thomas—not the Frank Thomas of a more recent vintage who is himself in the Hall of Fame and, yes, star of commercials for male-enhancement supplements. The Frank Thomas in question was a journeyman in the 50s and 60s pictured below.

Even with his ballcap off, I don’t know if Frank was molten or molting.

Thomas was an outfielder/first baseman/third baseman who in his career year hit 34 homers and drove in 94 runs—pretty respectable numbers, especially when you consider that he put them up as a member of the ‘61 Mets, the gloriously awful expansion team that lost 120 games.

By the time he came over to the Phillies in the mid-summer of 1964, Thomas was on a farewell tour and it looked like he’d have a shot at playing in the World Series, Philadelphia sitting pretty with a 5.5-game lead in the NL on September 1. Infamously, the Phillies cratered, losing 10 consecutive games in the stretch to finish a game behind St Louis. Having racked up 27 RBI in 35 games after coming over from the Mets, Thomas had suffered an injury around Labor Day—busting a thumb on the slide—and thereafter the Phillies reeled. Frank Thomas became Philadelphia fans’ If Only Man. The imagined narrative: If only he had stayed healthy, he’d have been the difference. (Highly debatable. The prevailing opinion among diamond historians holds that Phillies manager Gene Mauch, acknowledged as strategic genius but less highly regarded as a handler of pitching staffs, wore out his ace hurler Jim Bunning.)

In the season that followed, Thomas’s game fell off. In 34 games, largely in a backup role going into July 3, he was batting about .260, 6 RBI and no homers, in 82 at bats and hadn’t played in more than two weeks..

For his part was on top of Major League Baseball. On that day, July 3, he was named to the National League’s starting line-up for the All-Star Game. He was leading the NL in batting with a .335 average. To give you an idea of the company the 23-year-old was keeping: No. 2 in the NL stats was Willie Mays, No. 3 Hank Aaron, No. 6 Roberto Clemente. No mere contact hitter with his 41-ounce bat, perhaps the heaviest in MLB, Allen was hitting a loud .355, on pace for 25 homers and 100 RBI and was one of the most dangerous baserunners—he’d wind up leading the league in triples that season. He looked for the world like a first-ballot Hall of Famer, someone even fans in Philadelphia could help but love.

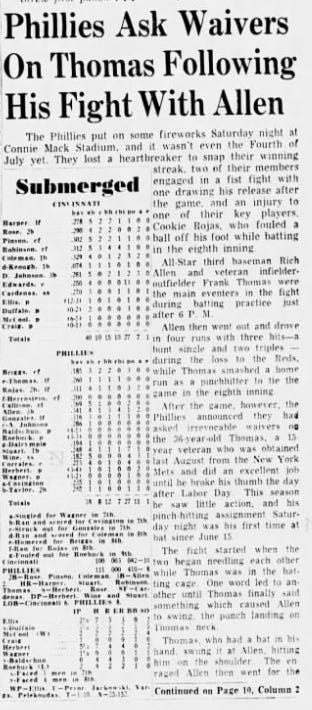

Fans who went to Connie Mack Stadium for the game that first Saturday night in July saw the Phillies drop one to the Reds. They’d have seen Richie Allen hit two triples in the game. If those fans stuck around for the late innings they’d have seen Frank Thomas enter the game as a pinch-hitter and hit his first homer of the season. But if the fans hadn’t arrived at the ballpark in time for batting practice, they’d have missed the real story though and would have been gob-smacked when they picked up the sports section on Sunday: The Phillies waived Frank Thomas after he and Allen had fought that night. Fireworks on the even of the Fourth of July. Here’s the account in the Inquirer on the holiday,

On Page 10 where this story continued, there was only a couple of lines about unnamed veteran players breaking up the fight and a synopsis of Thomas’s stint with the team.

Thomas in his brief time with the Phillies had become a fan favourite, but while he was waived for his part in the fight, Allen was given a talking-to by management and let it go at that. He was going to the All-Star Game and looked like the future of the franchise. Fans thought it was unfair they way it played out. Thus did Allen’s reputation as a trouble-maker start to take shape.

In the immediate aftermath, the media and Thomas though conspired to make the rep crystallize.

IN the pages of the Inquirer that year, no story in the Phillies’ season—the baseball season as a whole—would have been given the amount of space and play that the editors gave reporter Allen Lewin’s exclusive interview with Thomas in the July 5 edition: the better part of 1,500 words. Accounts of the biggest games of the season would come in at half that length.

I call Lewin’s story an “exclusive interview with Thomas,” but it could also be labelled “an interview exclusively with Thomas”—i.e., Thomas gets to tell his side of the story great length, the reporter managed to get only two words out of Allen when asked version of events. Quoth the young star: “What fight?”

I don’t know if Lewin bought Thomas’s account or if he torqued the story for maximum effect. Or both. Anyway you cut it, the story just inflamed the fans who held Thomas near and dear to their hearts and threw Allen completely under the bus—Thomas stopped short of dropping “uppity,” but blew every other racial dogwhistle, which would have been picked up by fans who fondly remembered pre-integration MLB. I transcribed Lewin’s story in full below the screen grab—and, yeah, no typo, Thomas was quoted as comparing Allen to “Cassius Clay-Muhammad Clay. [sic]”

Thomas Regrets Fight, Calls Waiver Unfair

by Allen Lewin / July 5, 1965

Frank Thomas, the 35-year-old utility man who was released by the Phillies Saturday night five hours after his fight with teammate and All-Star third baseman Rich Allen during batting practice, feels he is a victim of circumstances.

Thomas said he regretted his part in the affair in which he hit Allen on the shoulder with a bat, but that he regarded his being put on waivers by the Phillies because of the incident as unfair.

In an exclusive interview Sunday with the Inquirer, Thomas gave his version of what happened before the Phillies 10-8 lost to the Cincinnati Reds at Connie Mack Stadium. Asked for his side of the fight, Allen, whom Thomas charged with throwing the first punch would not admit anything took place.

“What fight?” was all Allen would say when questioned.

General manager, John Quinn, who said he was trying to get a replacement for Thomas, denied Sunday that the fight was entirely responsible for waivers being asked on Thomas.

“We had talked with one club in particular (about Thomas), trying to work out a deal without success— even before the trade deadline. So, it just isn’t the incident. As we said Saturday, for the best interest of the ball club, this is what we thought we should do.”

The request for waivers on Thomas followed a dramatic pinch-hitting appearance by the veteran who slammed a home run into the upper left field stands in the eighth inning Saturday night to tie the game, which the Reds won in the ninth.

Thomas, who was obtained last August in a waiver deal with the New York Mets and did a remarkable job as the Phillies’ first baseman until he fractured his right thumb the day after Labor Day, said of the fight, “I was wrong in swinging the bat, I’ll admit that, but it was just a reflex action.”

Fortunately, there were no serious injuries in the melee which followed the fight as teammates, tried to separate the pair.

Infielder Ruben Amaro, who had to be pressed into service at second base on Sunday because Tony Taylor had a sore shoulder, was hit by Allen in the scuffle as he was trying to break up the fight.

“My jaw was a little sore this morning,” said Amaro, rubbing the left side of his face. “But it wasn’t anything. I got hit here on the elbow by the bat,” Amaro added, pointing to his left one.

With Thomas out of uniform, Taylor hurt and Cookie Rojas limping as the aftermath of fouling a pitch off his left foot in the eighth inning Saturday night, the Phillies were hard pressed for reserves, although Rojas was in left field at the start of Sunday’s game.

“I just had a shot of painkiller, and I’m going to play,” Rojas said before the game.

Thomas said the fracas with Allen began with a lot of needling, which had gone on between the two and among other members of the team all season long.

“I’m one of the biggest agitators around, always have been,” Thomas said, “but I never tried to hurt anybody. I do it to try to keep the club loose.

“Certain guys can dish it out, but can’t take it,” Thomas said, obviously referring to Allen.

“When I came into the clubhouse Saturday, something was said about all the agitating that was going on, and I told (pitching coach) Cal McLish, ‘Tell those guys to stay off me and I’ll stay off them.’

“Well, when I went into the batting cage, Richie yelled down around third base, ‘Do what you did last night.’”

As a pinch hitter in the seventh inning, Friday night, Thomas struck out with runners on first and third and the Phillies one run behind in the game they rallied to win in the eighth on a homer Dick Stuart.

“I missed the pitch, and he’s laughing at me. Then, I fouled off a bunch, and then bunted down the third baseline.

“At that, he yelled, ‘That’s 21 hours too late.’

“They were laughing, just like a while back when I was at third base and somebody hit one at me in batting practice just as I turned around it hit off both my legs as I reached down for it.

They were laughing like anything. I had to go in and put ice on my legs, though I wouldn’t give them the satisfaction of rubbing them out on the field.”

Getting back to Saturday night, Thomas said Allen began calling him ‘Lurch,’ a nickname Rich hung on Thomas a while back after the Frankenstein-monster-type character in the television show, ‘The Addams Family.’”

“He started calling me, Lurch, and we yelled back-and-forth, and that’s when I said, ‘You’re getting just like Cassius Clay-Muhammad Clay— always running off at the mouth.’ Then he said something about coming down, and I yelled, ‘If you want me, I’ll be here.’

“‘I’ll be down,’ he yelled.

“He came up to me and asked, ‘What did you call me?’

“So I told him, and I said, ‘If I hurt your feelings, I’m sorry.’

“‘That don’t go with me,’ he said, and then he swung and hit me in the chest.

“I was surprised, I had the bat in my hand, and I hit him on the left shoulder. It was just a reflex action.”

At that point, Allen became enraged, was grabbed by five or six of his teammates, and was pushed and wrestled back near the permanent backstop behind home plate.

“After it happened, I went over to him—[Manager Gene] Mauch had his arm around him—and I felt real bad because I could see he was hurt.

“I went up to him and said, ‘I’m awfully sorry, Richie. I want to apologize.’

“Then in the clubhouse, I went over and apologized again, and he said ‘Get away from me.’

“OK, if that’s the way you want it,” I said.

“My stomach didn’t feel good all night. I went up to the training room. He was up there, and I could see how much his shoulder was bothering him.”

Thomas felt worse after the game when Mauch called him into his office, and told him about the club asking waivers on him.

“When he told me,” Thomas said, “I asked him if the incident tonight was the cause.

“‘If so,’ I said I think you’re being unfair. We’re always agitating each other and he hit me first.’

“‘You’re 35, and he’s 23,’ Gene said, and I asked what that had to do with it.

“I told Gene, ‘You’re always ready to fight back. You know that yourself.’

“When he said I shouldn’t have hit him with the bat, I said it was just a reaction.

‘If I hadn’t had a bat in my hands,’ I told him, ‘I would’ve gone after him with my fists.

“But I’ve always liked Richie, and I’ve tried to help him. This was just one of those things.

“Right from the start of spring training, this has been coming, I guess,” Thomas said, referring to his release.

“Mauch tells me one thing, then does another. I could never find out where I stood.”

When it was mentioned that this incident will probably revive the many false rumours that have been floating around for a year about clubhouse fights on the Phillies, Thomas agreed.

The veteran said, “They’re haven’t been any real arguments that I know of. Oh, maybe one or two, but I never saw or heard of any fights while I’ve been with the club.”

Thomas, who had a meeting with Quinn Sunday morning, wasn’t certain about what happened to him pay wise, but the general manager explained:

“We have asked National League waivers only,” Quinn said. “That means if any club in the league claims him, the lowest one in the standings will get him for the waiver price of $20,000.

“I’m sure one club in the league will take him. If they don’t, then we’ll ask waivers for the purpose of giving him his unconditional release. Then, if no club claims for one dollar, he’ll be free to make a deal for himself and that is the only time he’ll get 30 days’ pay. Until that happens, his regular page just continues.”

Thomas is hopeful some club will pick him up.

“I have to wait around until Friday until the waiver period is up,” said Thomas, who took his release, philosophically, but still with some regret at leaving the Phillies.

One last harmonious postscript to the whole affair occurred in the eighth inning Saturday night when Thomas returned to the dugout after hitting his homer.

Among those who shook his hand in congratulations for the big blow was Allen.

Okay, a lot to process there.

The reporter gave Thomas every benefit of the doubt and Thomas pulled out the stops in trying to lay all blame at the spikes of Allen. This was a case of self-defence with a bat. Allen was so irrational

The “some guys can’t take it” business is pretty hard to take, given the offence Thomas seemed to take from being called “Lurch,” which to me is about as benign as it comes.

Landing twice on the fact that he had in fact hurt Allen, Thomas was trolling Allen—it’s almost as if he couldn’t help himself.

Thomas made it sound like it was his bad luck to be holding a bat when the matter escalated. The reporter seems to have just taken dictation on this one and left unasked the obvious question: “If you were so ready to mix it up with your fists, why didn’t you just drop the bat?”

Purely a historical footnote and do with it what you will: Before the Pittsburgh native signed a contract with his hometown Pirates, Thomas had chosen to pursue priesthood and spent four years in a seminary in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Talk about going the other way.

In the immediate aftermath the Phillies had told Allen not to speak to the media about the fight—the “What fight?” line was John Quinn’s directive and it would have covered everyone in the Philadelphia clubhouse. Allen didn’t push back against it and neither he nor any of his teammates leaked the account to the reporters. No matter, rumours filled the void and just about all painted Allen in the worst possible light.

After Thomas gave his account to the Inquirer, the Phillies had no choice but to do damage control—the narrative was getting away from the Phillies and Quinn had to protect the budding superstar. (According to Merchant in the audio below the paywall, Quinn was a fan of Allen and was practically popping champagne when the team signed him out of high school in Wampum, Pennsylvania.)

In his column of the 6th of July, Merchant splits the difference. There is no good guy, no bad guy here, no Boy Scouts, no scoundrels twisting wax moustaches. As he lays out, this was once again “fratricide or animated Philadelphia scrapple.” He went on: “The fans boo their own heroes, especially Hero No. 1. The last few nights they have been booing the hell out of Richie Allen.”

From Larry’s column:

“I'm sorry about the whole thing,” Allen said. “I'm really sorry. I should have thought it over in the heat of a pennant race tempers flare. I know it won't happen again.” He said he was sorry they put Thomas on waivers “but I don't work in the front office.” He hoped he got a job.

Asked about his mother, who raised him with a firm hand, Allen said, “She was upset. She told me, “Dick, you always were trying to fight. It's time he settled down. Tempers with the boys are about as short as fingernails.’”

Later Allen amplified some of his statements and shed darkness on others.

He said he wouldn't accept Thomas’ apology after the fight “because I was still mad.” He said he said the published version of the fight wasn't accurate, “but I won't say anything that might hurt him to get a job.” He refused to give his version. (Eyewitnesses have substantiated Thomas’ version.) Allen said he had many fights in high school. “I've been fighting all my life,” he said. “Fighting for life, fighting to live. My mother's punishment for fighting or anything, was a good whaling. And believe me I took many of them.”

The verbal whaling he is taking from the fans doesn't bother him, he said. It's not as bad as Little Rock where he was the target of racial insults. “I like the booing he said. If they don't boo nobody knows I'm here. It's just a booming town. That's its nature. They’d boo Willie Mays here.”

Sounds a lot more genuine and from the heart than Thomas’s version.

In a Daily News column two weeks after the fight between Allen and Thomas, Larry was still responding to reader mail and public sentiment seemed somewhat divided. The scribe didn’t buy the line that the players’ talents and future prospects should have factored in the decision. He pointed to Thomas's bad-ass agitator mode and made it sound at once something baked in his cake but also something that could be worked around: Larry laid out an account of Pumpsie Green, another Black ballplayer, who had asked to borrow Thomas’s bat the season before. Holding his bat yet again, Thomas said, “You’ll have to take it for me.” Green appealed for civility—can’t we be grown up about this—and Thomas gave it over to him, fee

In Philadelphia to boos for Allen drowned out cheers, as boos always do in the city. The boos won’t in Cooperstown this summer when Allen’s survivors and friends will be there for his induction, wishing like I do that he could have been around to hear only cheers.

Thanks for reading. Below the paywall is a 50-minute conversation I had with Larry Merchant this week. As an HBO commentator, Larry was never in a race to talk, always gave thought to every word. He hasn’t sped up the pace at all in his 90s. His insights and memories remain keen though—he’s on point about Allen’s history on and off the diamond and the Phillies’ regrettable record on Black ballplayers (the last team in the National League to integrate, more than ten years after Jackie Robinson). If you’re a regular on How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) or intrigued by any of this, sign onto SubStack and come to How to Succeed later on—I’ll post additional content with this piece.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.