No. 278: PAUL RIMSTEAD / My inopportunely timed conversation with the scribe who walked away from the job I dreamed of (& then drank himself senseless and worse).

A chapter in rough (or a rough chapter) from my upcoming memoir.

I am just wrapping up a book, an adaptation of my memoir for Audible, that eight-hour gaze in my career’s rear-view mirror that gave this SubStack its unwieldy name and its dubious raison d’être. (I started this SubStack to excerpt and promote the audiobook.)

When I call the book “an adaptation,” you might think that’d be just a heating-up and seasoning of what’s left over from the telling of my sportswriting life available at a very affordable price on Audible. Not the case at all. For my publisher, ECW, to qualify for the government arts funding, my adaptation was going to require 90 percent original material between its covers. Yeah, effectively my direction was along the lines: “Tell your life story again, but, y’know, with all different stuff.”

On its face, a fool’s errand, an impossibility. I only tried because what I wrote and read out loud for Audible was directed at an American and international audience, readers/listeners who’d be interested in famous names I interacted with from the NFL, the NBA and MLB. I was kinda stingy with hockey stories in the Audible Original—Pat Burns got in there, ditto the kids who sat in the stands at a junior draft until he was selected with the 391st pick and ditto dining with the media-hostile Tom Barrasso, who kept sending back $800 bottles of wine at a restaurant managed by a close friend of mine. Still, I kept it hockey to a minimum.

A puck-focused, rink-world variation of the Audible memoir, that I thought was not only doable but would land with readers and satisfy the folks on the arts council. The feds want Canadian content, I’ll give them Canadian content.

It will be a different book to be sure. For one thing, after a fashion it starts and ends at Maple Leaf Gardens. The earliest memories track back to my first game at MLG, Leafs hosting Boston, which happened to be on the day the Bloor-Danforth line opened on the Toronto subway system. Action in the book ends with working the last game in the Gardens … I won’t dig down on detail there today. Maybe down the line.

The memoir’s working title at this point is Portrait of the Artist as a Young Scribe. We’ll see if that survives. Susan, my pro bono editor in the home office of Gareco Enterprises, hates it. Friend of the H2SiS(wRT) SubStack Bill Scheft (ex-scribe, ex-Letterman head writer) backed me up, suggesting that I earned the right to appropriate the title after being asked pretty much every day if I’m related to James Joyce. (Yes, sigh, it happened again just yesterday. Everyone’s a smartass.)

I had to come up with an elevator pitch for ECW last week, something to take to the sales department. This is what I came up:

“Most kids dream of becoming sports heroes, but Gare Joyce realized early on his only chance of getting up close with greatness was with a notepad, a pen and a press pass. Going behind the scenes with the famous names, rich in the stories the media doesn’t dare to tell, this memoir is, by turns, a coming-of-age in the press box, a love letter to sportswriting and a cautionary tale about getting what you wish for.”

Anyway, today’s offering is an excerpt drawn from my first draft—if it jars at the start, understand that it’s in media res. The text focuses a media figure known best to folks in Toronto of a certain age, Paul Rimstead, who was an accomplished and celebrated sportswriter who threw sports mostly aside when he became the Page 5 columnist of the Sun, when it rose out of the ashes of the Telegram 54 years ago. Without further ado, here’s the draft, forgive the typos. (I’m going to throw the payoff behind a paywall today and tomorrow I’m putting the whole item on subscriber-only status so, for non-subscribers, enjoy what you can while you can.)

DON’T IMAGINE THAT YOUR EDITOR IS THE ONLY THING THAT CAN CATCH UP TO YOU

… I didn’t meet one of the Sun’s best-known columnists in my time at 333 King Street East—a pity because I had questions for Paul Rimstead.

As the owner and proprietor of the Page 5 column, Rimstead was beloved by management, those who had worked with him at the Star and the Telegram in his glory days which predated the summer of love, and he was envied by the rank and file, less so for his salary, which dwarfed senior reporters’, and more for his license. He had a free hand and could get away with what no one else dared to think about.

Rimstead was considered the ultimate industry success story—a high-school dropout from Bracebridge, who had bounced from the Elliott Lake Standard to the Sudbury Star to the Kingston Whig-Standard and then on to the Big Smoke, to work at the Globe and Mail and the Telegram and the Star. If you were looking for his breakout moment—in wrestling terms, when he got over—you’d point to a relatively short-lived stint writing sports features for Canadian Magazine, the weekly supplement in the Star and other dailies around the country.

Rimstead’s longforms in the 60s might not have been up there with features penned by the famous names at Sports Illustrated and lacked the flourish and wordplay of Roger Angell’s paeans to baseball in the New Yorker. Rimstead’s prose was prosaic and he didn’t always stay out of the way of his subjects—he’d talk about his friendships with some, about acting on his desire to help out those in straits, about knocking back drinks with the stars. He was the fourth-estate chronicler and celeb wingman.

These knocks notwithstanding, his stories stand up lo these decades later. If sometimes objectivity and a professional distance had to be sacrificed to get inside, he’d make that deal every day of the week. If it bothered you to read about his late-night phone calls with Carl Brewer, the Leafs mercurial and tormented All-Star, he dared you to stop reading. What you’d find in his story you’d find nowhere else.

Decades after it ran, I looked up and pored over a story that Rimstead wrote about Bruce Draper, a forward with the Hershey Bears who was trying to come back after treatments for lymphatic cancer. This was a profile and elegy in one, an obituary for the still living. Rimstead laser-focused on a game between the Bears and the Providence Reds at the Hershey Sports Arena, Jan. 11, 1967, Draper’s first game back in the line-up after treatments that had wasted his body but not broken his spirit. The prognosis for Draper had been dire and though he made it back into the line-up, he wasn’t out of the woods—he skated that night with the foreknowledge that his chances of dying within two years were likely if not certain.

The display on the piece was gutshot stuff and truth in advertising: “The goal that death was watching.” Some of the prose clangs—“one of the most dramatic moments I’ve ever seen in sports” and “a story of courage and a young man’s faith in God” feel unnecessary. And Rimstead’s recreation of scenes inside the Bears’ dressing room before the game strain credulity and likewise the dialogue feels forced.

“Hey you guys!” boomed Bruce Cline, an assistant captain. “Looks like we have a rookie with us tonight.”

But even cliché can’t blunt the force of the storyline, which was Brian’s Song, albeit with events unfolding before Brian Piccolo landed on the Bears’ roster to back up Gale Sayers.

It would be nice to finish this off by saying Bruce Draper won back his spot on the team and became an all-star in the second half of the season. But this isn’t a fairy tale. This is life.

He may be back in the Hershey line-up when this is published, but the fact that Mathers decided to replace him after two games because he felt Bruce wasn’t strong enough to help the team.

And I mention the minor flaws only to make the point that they don’t matter at all.

The detail of Draper’s physical agonies and spiritual testing left me emotionally spent by the time I made it to the last line, words from Draper.

“Hockey is secondary. I said that from the start. First, I want to live.”

Draper did live. For 53 weeks after his last game.

I read Rimstead’s pieces in that weekend supplement when I was in grade school. He had the job I longed for. I couldn’t imagine that he’d ever want to do anything else.

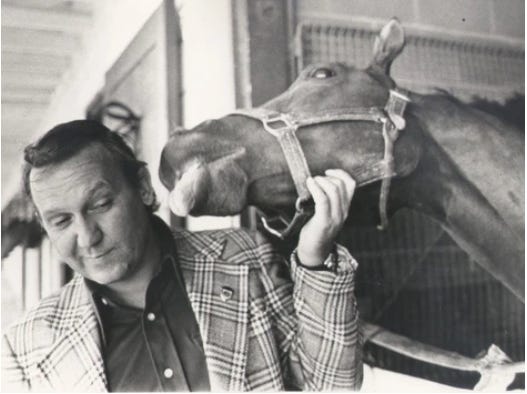

The headshot that ran forever with the Page 5 column.

And yet when the first edition of the Sun rolled off the presses on November 1, 1971, Rimstead was there on Page 5, a column with a headline that read “Hello, SUNshine!” and a headshot that looked like it had been captured rousing Rimstead the morning after the night before. Exactly what his topic that day

“From the outside, it doesn’t look like much. And frankly, it is even worse on the inside.”

Rimstead walked readers through an improvised newsroom with the former Telegram employees who turned around a full tabloid from scratch in 24 hours and put it on the city streets overnight, an enterprise that might not sound like much as you read it here but is akin to performing brain surgery while wearing hockey gloves and wielding butter knives in lieu of scalpels. The inaugural column established a cast of characters—that’s what the Sun had, not executives with MBAs, not crack reporters nor expert columnists, but rather characters, a collective comprised of ragged castoffs, kids and old hands who weren’t going to take any shit. Rimstead was recruited to be the city columnist, what you’d assume to be the vox populi, but on that day, as he often would be ever after, he served as the voice of those behind the scenes—before he could tell stories in the paper, he had to tell the story of the paper. At the end of that first column, he wrote:

This is going to be the most exciting experience any of us have had and it gives you a good feeling to sit amid the debris and think about it.

More than anyone could be or could want to be, he was the writer with a toolkit and inclination to file from the debris. Where there wasn’t debris, he’d create some, leave some.

LIKE Dick Beddoes only more so, Rimstead became a character in his stories and cooked up stunts that he milked for all their worth and then some. Because of his late entry, his run for the Toronto mayoralty only provided fodder for a three-week run of stories. This, of course, cribbed Jimmy Breslin’s act when the New York Post columnist ran for mayor. While Breslin frequently wrote about city hall and the public interests in the metropolis, Rimstead seemed uninterested in politics in general. His mayoral platform was not strategic, but the random thoughts of a barfly jotted down on a cocktail napkin: Yonge Street is a mess; the mayor and city councilors should be paid half what they were making, if at all; and people should be decent to each other. He vowed he’d never go in city hall if elected. Rimstead finished fourth.

The best-known example of his stunt journalism carried over from his days at the Canadian Magazine: In 1968, Rimstead bought a sad thoroughbred christened Annabelle, entered the filly in claiming races at Woodbine and Greenwood where she ran laughably last, and vowed to enter her in the Kentucky Derby, the impossibility of such a bid not likely occurring to his readers. She was, like he had been, an unloved underdog who’d have been left behind, destined for the glue factory. Instead, Rimstead loaded Annabelle into a freight elevator and led it into a banquet room at the Royal York, where he had gathered investors who bought shares in the horse for $1, with a limit of one share per patron. He didn’t limit shareholders to celebrities, but it didn’t hurt, with Olympic champion Nancy Greene and golfer George Knudson among the invited. In no time the list of the also-ran’s owners read like the Order of Canada and the story was picked up in Sports Illustrated and other media in the U.S.

As was the case with most antic Rimstead escapades, the wind-up outstripped the payoff. Annabelle never made it to Churchill Downs and never even won a claiming race, only once finishing third in the race. No matter. Annabelle lived into her equine dotage and on a slow news day years later at the Sun he’d pay a visit to the mare in her stable and treat readers to raked-over memories and an account of a day in a horse’s life. Yeah, for the storyteller, Annabelle had a long tail. Though I never got it, but readers in the day apparently ate it up as an improbable love story, devotion requited with defeat. The takeaway: People still pull for the underdogs a decade after they run their last lost races, and this columnist wrote for the most soft-hearted slobs.

One of the lesser-known McMahon’s in wrestling before Rimstead renamed him.

Though not as well remembered was Rimstead’s entry into the world of professional wrestling. The fit was a natural one--if not a real showman and entertainer, Rimstead was at least a self-styled one. He lacked the physical stature to enter the ring wars himself and didn’t want to put his hands in harm’s way, lest an injury interfere with his jazz drumming and occasional typing. The columnist found a surrogate in Pat McMahon, a truck driver and construction worker from County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. A two-legged Annabelle with a brogue instead if a neigh, McMahon had boxed in the army and upon coming to Canada trained for hoped to break into the pro game. Rimstead took on McMahon and immediately rebranded him. McMahon became Shillelagh O’Sullivan, the name drawn from a Bing Crosby song telling the tale of an Irish cowboy who eschewed a holstered sidearm and instead wielded an Irish walking stick. Rimstead assembled an entourage for the wrestler, including a Irish tenor breaking into “The Wearing of the Green” and a little person decked out as a leprechaun. O’Sullivan wrestled five times at the Gardens, but never made it to a showdown versus the villainous Sheik, the headliner who went undefeated for years. Predictably Rimstead tired of it as quickly as his readers and he moved on from McMahon, who wound up back on the construction site, while the tenor went back to waiting tables and the little person to his job as a greeter at the Inn on the Park.

Yeah, the madcap stuff didn’t always land, but there was always tomorrow’s column. If something worked once it was worth doing it again, until there was no juice to squeeze from the lemon.

EVERY newspaper has a particular culture and the Sun had the aspect of a team, maybe even a cult—those who bought in didn’t work for the paper, so much as belong to it, the front-page banner tattooed across their ventral side. Standing atop the Sun newsroom’s hierarchy were the Day Oners, that noble lot who populated Rimstead’s inaugural column, who got the paper out on Halloween night, 1971. They weren’t simply acknowledged and respected, but rather honored or at least expecting to be honored by the later arrivals and the newbies like me in particular. Colleagues’ eyes would grow damp in appreciation of their daring and sacrifice. Yes, if this were a Remembrance Day parade, the Day Oners weren’t just veterans of the Great War, but those who served with highest distinction, decorated warriors of the Dunkirk, Dieppe and D-Day.

If you bought into the legend, then Rimstead was a hero of a higher order, Winston Churchill, George S. Patton and Richard Rohmer, rolled into one, though he’d probably prefer Major John Reisman, the cool centre amid the mayhem as played by Lee Marvin in The Dirty Dozen. That wouldn’t reflect his style or shlubby bearing or role, but it would capture his self-congratulation.

I didn’t buy any of it. The lore didn’t mean a thing to me – I was the last in the door and aspired to work for the broadsheets, to the Day Oners and hardcore loyalists a pretention that stamped me a heretic.

By the time I made it to journalism school, I’d flip right past Page 5. I had no interest in reading about Rimstead’s latest stunts. I cared not about his girlfriend, Miss Hinky, or Texaco Joe, the owner of the gas station near his cottage, or any other longtime recurring character. His continue employment at the Sun was a mystery to me—supposedly, readers ate him up and he made a point of thumbing his nose at elites, though I hardly felt like one, making $200 a week and going to school by day. Even more puzzling to me, though, was why he set aside sportswriting—oh, hanging out with Eddie Shack, the clown prince of the Maple Leafs, and writing about him filming a commercial for Pop Shoppe doesn’t really count as sportswriting.

At Canadian Magazine Rimstead had the greatest gig in the world, the one I so desperately wanted, and could have written his ticket with any sports section in the country. Instead, he walked away. If I ever had a chance to sit down and talk with him, I’d work my way around to that question. I wouldn’t rush headlong into it, mind you, because that might be impolitic if not impolite—maybe something went sour, maybe there’d be pain, maybe regret. I’d ease into it …

I never did find out.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, I didn’t meet Rimstead in my time at the Sun, but I did speak to him when I fielded his phone calls to the city desk. Editors didn’t want to give him their direct numbers—this was the era before Caller ID, so there’d have been no screening calls.

The first call was as much of a conversation as I’d ever have with the man.

“It’s Rimstead, who’s this …”

I started to explain who I was. I figured I’d shoot him a line about me being one of the little people, those who loved him, presumably anyway, and those he wrote for. He cut me short, which is to say right after “Gare” and before “Joyce.”

“Do I know you?”

I tried to explain that we had spoken before. Back when I was sending out applications to journalism schools, I picked up a few shifts at the liquor store on Parliament Street, the last location in Toronto to have counter service for goods, a precaution needed due to the seediness of the clientele in Cabbagetown, shoplifting rummies, in those days before the neighborhood’s gentrification. Rimstead would come in daily, and I’d fetch him a 26er of Cointreau, his drink of choice at the time, an express ticket to diabetes. At the counter I’d butter him up, mentioning that I had read his column on that given day, but that never got more than a forced smile out of him—I just presumed he lacked comfort with his celebrity in the venue and just wanted to go about his business.

“We talked when I used to work at …”

I got no farther.

“Gimme somebody.”

He didn’t have the time of day for me. In the newsroom I was a minnow, and he only dealt with marlins.

When I turned around and there was another O’Sullivan, Peter O’Sullivan, whose forebears would have tracked back to County Cork, but he was as English as high tea. I asked him about his bloodlines just the once—he was one of the few editors who gave me the time of day, although it came off as charity—and he said, “Liverpool Irish” and sighed, like it was his cross to bear. There wasn’t anything Liverpudlian or Scouse about him, even though his first job out of college was in the newsroom of the Echo, the Merseyside’s favorite tabloid and there, at an age younger than mine at the time, he was anointed a boy wonder, a wizard in tabloid editorial strategy, destined for greatness. O’Sullivan was in his early 30s, but he gave off an older vibe, the adult in the room. When publisher Doug Creighton appointed him as managing editor, the old hands who had waited their turns could only shrug and drown their sorrows, running up their considerable tabs at the Press Club.

There they’d never run into O’Sullivan, who wasn’t of the Sun in many ways. Rimstead had a lot of company who also made a party of publishing the daily, but O’Sullivan was reserved. In print, columnist Christie Blatchford described him as “painfully shy” and that was a fair estimation. O’Sullivan sounded like the man from the Times of London—if you were going to cast him, both in look and manner, think of Anthony Hopkins in The Elephant Man.

Which is to say, Peter O’Sullivan prided himself on a professionalism and thus was about as far away from the fiercely anti-intellectual Paul Rimstead as anyone in the newsroom.

“Peter, I have Rimstead on Line 4,” I said. He was on a call and cupped his hand over the receiver.

“Give me a minute and patch him through,” he said with a shake of his head and a roll of his eyes.

I got back on the line with Rimstead.

“Peter O’Sullivan is just wrapping up a call,” I said. “Just a second and I’ll transfer you.”

“Tell him …”

And there the words stopped. A few seconds passed.

“Hello, are you there?” I said. Don’t tell me I lost him. Shit, I’m going to get blamed for something.

Then he came back on the line.

“… that it’s …”

And again, a break of seconds, but I could tell the call didn’t drop. I could hear Rimstead breathing. Heavily.

“… it’s Rimstead …”

Same routine.

In that silent break, Peter gave me the all-clear signal.

“One second, transferring,” I said.

No response from Rimstead other than some guttural noise.

“I think he’s sick or having a heart attack or something,” I said to Peter before he picked up.

“Peter O’Sullivan here,” he said. And at that point he tucked the phone between his ear and shoulder and typed in fits and starts. I put together that Rimstead was dictating his column off the top of his head with Peter taking the role of stenographer. Within a minute or so he looked stricken.

Rimstead’s m.o. was pushing boundaries. Once, a binge in Mexico that incapacitated him for the better part of the month amounted to research for a column that began: “Where have I been? I have been drunk. I have been drunk for three weeks.” Oh that rascally Rimmer! Another time he dictated a column that had run in the paper years before and claimed it as original—what would have been a firing offence for others (see Dick Beddoes) resulted in a two-day suspension for Rimstead and, yes, fodder for other columns. There he goes again.

I didn’t imagine that Rimstead was at it again when I transferred the call over to O’Sullivan, but I did wonder what was going on. I glanced at the editor and, as he stayed on the line and typed, his jaw slackened.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.