No. 268: BOBBY HULL'S BRAIN / I was labelled an armchair expert. "He's no neurologist." Years later, the forensics finally caught up to my biography of hockey's disgraced star.

I wasn't crawling out on a thin limb when I suggested Hull might have brain damage. Nor am I taking a victory lap with yesterday's reports confirming what I wrote back in 2010.

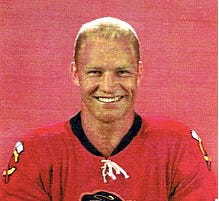

Robert Marvin Hull in his heyday & in his dotage.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.