No. 256: ALEXANDER OVECHKIN II / I didn't know I was watching a 16-year-old who'd one day break Gretzky's career scoring record, but everyone knew he'd be a force in The Show

I'd never profess to being an expert, but you didn't have to be to recognize that young Ovie was a man among boys at the 2002 under-18s in Piestany.

A TransWorld Sports interview with Alexander Ovechkin, 18, in Moscow in March 2004, ahead of the NHL draft.

On Monday, I wrote about Alexander Ovechkin’s North American debut, four games with the Russian team at the 2001-02 world under-17 tournament. You might have missed it even if you were around the corner from the arenas where the games were played, which would have place you in Selkirk and Stonewall, Manitoba. According to the accounts of a couple of friends who were at the game, the few who came out were fellow members of the fraternity of NHL scouts. Check out No. 255: ALEXANDER OVECHKIN / When the greatest goal-scorer in hockey history made his North American debut …

In No. 255 I also worked in the fun fact that Alexander Ovechkin’s name first appeared in a North American newspaper in June of 2002 in the Ottawa Citizen, a one-time mention in a feature I wrote about Russian prospects squeezing North American agents for small ransoms in advance of their draft years and those same prospects butting heads with friends of Putin who owned teams in the KHL. I would never claim that “Feeding the new Russian Revolution” is artful in anyway, but I think it gives some decent insights into what was going on behind the scenes with that first generation of Russian prospects who had a (fairly) clear path to the NHL. You’ll find a lightly reworked version of that intrigue-rich piece below the paywall—it makes for light reading.

In the Citizen story there’s a line noting that Ilya Kovalchuk’s rookie card was going for $1,000 coming off explosive first season with the Atlanta Thrashers, understandable at the time given that he had skated with the Russian Olympic team at age 18. I looked online this week and found that card in 9.5 condition, i.e. pristine, can be yours for $300. If you’ve ever wondered why Kovalchuk failed to live up to such early promise, well, there are no definitive answers but a lot of clues in that piece back in 2002.

Today, though, I’m going to dwell on the first time I had a chance to eyeball Ovechkin: the 2002 world under-18s in Piestany, Slovakia. I’ll try a bit of an alternative approach today: an annotated excerpt from The Ovechkin Project, the unauthorized biography I co-wrote with Damien Cox of the Star back in 2010. (1) Wherever there’s additional info to glean I’ll attach a numbered footnote, just like I did in the preceding sentence.

So here’s the excerpt. (Don’t imagine that I’m trying to promote sales of the book. It has been out of print for a decade at this point and if there’s an online version of it, Damien and I will never see a nickel from it.)

The world under-18 tournament, a spring fixture on the IIHF schedule, is always the most intensely scouted of tournaments because it serves as a showcase for elite prospects eligible for the NHL entry draft two months later. So it was in April 2002. Dozens of NHL scouts and several general managers booked tickets to Piestany, a spa town in Slovakia that was hosting the tournament.(2) They wanted to get a last hard look at 1984 birthdays.(3) They also wanted to get a glimpse of the Russian kid who wasn’t going to be draft-eligible for another two years.(4) Some of the scouts and a few executives who had been to Russia knew about him—they knew that this kid, just in his middle teens, was dressing for Moscow Dynamo in the Russian elite league, but it mostly seemed like a novelty to them. With Dynamo he only would get a few shifts in games against professionals, no opportunity and no fair measure of his talent.

Those who knew the teams and players best rated the Russians as the tournament’s most talented outfit. That said, the insiders considered Ovechkin’s team a co-favorite with the U.S. and the Czech Republic, because the Americans’ and Czechs’ team play was much better than the Russians. History had been turned inside out. The old Soviet teams were the Big Red Machine, its parts interchangeable, its play unselfish—if Soviet players had been criticized for anything, it wasn’t for hogging the puck but rather for over-passing it. The Russian team at the 2002 under-18s was a stark contrast to the ones that had worn CCCP. The Russian teenagers in Piestany were well aware of the NHL scouts in the stands. Their agents were in their ears, telling them how their performances at the under-18s would factor into their chances to make millions in the NHL. In this way, many of the Russians approached the tournament less as a contest of merit and more as an individual showcase. As talented as Ovechkin and team-mates were, those following the tournament with a professional interest thought that selfishness would hurt the Russians’ chances.(5)

The Russians did live up to their billing in an 8-4 victory over Canada in the first game of the tournament.(6) “They were easily the best talent there,” a scouting director with a Canadian-based NHL team says. “Ovechkin was very good but the first player who got my attention was Nikolai Zherdev. It was just his skating. Ovechkin looked like a very good skater—it would be one of his strengths as a NHL player. Zherdev, though, could fly. His speed would put him in the top one or two percent of guys in the NHL. There wasn’t anyone in the tournament that could stay with him. He would get the puck and pass everyone on the ice.”

Many scouts had the same first impression but, as Russia rolled through the tournament undefeated and only challenged a couple of times, they noticed that Zherdev carried the puck right by opponents and team-mates without a glance. The criticism of Ovechkin at the under-17s was that he “could have used his linemates more” but Zherdev didn’t even seem to notice them—neither team could get the puck off him.(7) By the end of the tournament, Ovechkin’s talent thoroughly over-shadowed Zherdev’s—scouts considered the Russians’ youngest player to be the soundest, least selfish prospect in their line-up. Ovechkin again led the tournament in scoring with fourteen goals and four assists in eight games. His Russian team-mate and future Washington Capitals sidekick Alexander Semin was second in tournament scoring with eight goals and seven assists.

It was a glorious stretch for Ovechkin. (On the IIHF scoresheets, he was now Alexandre Ovetchkine.)(8) It all came apart, however, in the final game of the tournament. Russia only needed a tie against the U.S. to come away with the championship. Though coming off a shutout loss to the Czechs, the Americans could win the gold if they managed to beat Russia—or if the Russians managed to beat themselves. That’s what happened. The final score: U.S. 3 Russia 1.(9) As time wound down in the game, Russian players seemed to take turns in trying to win the game with coast-to-coast rushes, bypassing open team-mates. Led by future U.S. Olympians Zach Parise and Ryan Suter, the Americans played a tight defensive game and looked to quickly counter Russian forwards who chased the puck too deep and to exploit Russian defencemen who pinched too often seeking their own bit of glory.

Even with the silver medal, the Russian team under-achieved, but those scouting for the NHL viewed Ovechkin as blameless in the loss. He was the player of the tournament. NHL teams had to wait; the agents couldn’t. They had been in the crowd in Selkirk and Stonewall. They were in Piestany. They were going to follow Ovechkin back to Moscow.

Okay let the footnotes begin.

(1) Saying the book was “unauthorized” only hints at Ovechkin’s lack of direct involvement. Originally he seemed interested if not eager to get his story out there and to talk to us. When Damien and I arrived in Washington, though, the star of the show put us off until later—no big worry. After all, we had arrived on the scene just as the snowstorm of the century had fallen on the region, effectively shutting the capital down. The postponement of a Sunday early-afternoon game against Sidney Crosby and the Penguins was a very real possibility, what would have been a disaster for the league given that it was timed with Super Bowl Sunday. Damien and I worked our way through interviews with all his teammates and everybody else in the Capitals’ world—I drew the massage therapist. Alas, somebody in Ovechkin’s inner circle put the kibosh on his speaking to us without a piece of the action and with that, presumably, approval on the text. A non-starter. I felt the tag of “unauthorized” didn’t diminish the book—in fact, I made a case that it could have been used in the book’s marketing, maybe even on the cover. I was out-voted on that one. Our access was fairly limited to what everyone else could get in scrums, but no matter—it was an epic write-around, but so was “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” Gay Talese’s epic profile of the star in the September of his years. I don’t know that the book insults Ovechkin, but it’s certainly not hagiography, anything that Capitals’ media-relations department would have cranked out. As the dog wagged by the tail, Capitals’ owner Ted Leonsis disparaged the book upon publication, even though he had spoken to us pretty freely pre-publication and okayed unlimited access for us.

(2) Yes, Piestany was the site of the 1987 world under-20 tournament and the infamous bench-clearing brawl between the Canadian and Soviet teams in the final game. Those teams and that fight were the subject of my book When the Lights Went Out, published in 2006. Hard to believe that it has been 19 years since I was talking with Pat Burns or landing in Belfast to chase down Theo Fleury, who was playing for Northern Ireland’s team in British League.

(3) Eligible players had to be morn after January 1, 1984. Ovie was born September 19, 1985 birthday and thus 21 months younger than the oldest players in the tournament. The breakdown: Most players in the tournament were eligible for the 2002 draft; a few (those born between September 16, 1984 and September 15, 1985) were eligible for the 2003 draft, among them Zherdev; Ovechkin was a standalone, not eligible until the 2004 draft.

(4) Ovechkin was missed the cutoff birthdate for the 2003 draft (September 15, 1985) by just two days. The date has been determined with the idea that players have turned 18 in advance of the NHL training camps. In one of the goofiest moments in draft history, then Florida Panthers GM Rick Dudley called Ovechkin’s name with a late-round draft pick. Dudley tried to make the case that had lived 18 years … if you played with the numbers and gave him extra credit of a day for every leap year. To what degree Dudley thought that he could challenge the letter of the NHL regs I dunno—and I know Rick pretty well. It went nowhere. League officials nixed the pick.

No matter how much my friend Duds worked the phone there was no budging the league on the definition of “a year.”

(5) This group of U.S. players (line-up linked here) was the first group to come through USA Hockey’s under-18 program which was then based in Ann Arbor. (It moved to Plymouth a few years back.) The success of Parise, Suter et al at this tournament and the same core group’s win at the world juniors in 2004 (the first gold at the tournament for an American team) set the table for the development of what is now the model player-development program. Including the 2004 tournament, the U.S. has won seven golds at the under-20s over the last 21 years, second only to Canada’s 10.

(6) This tournament marked Canada’s first appearance at the under-18s. Hockey Canada didn’t send a ream prior to that, because of conflicts with the CHL playoffs. The 2002 team was drawn from players whose teams missed the playoffs. The most notable player in the Canadian team’s line-up was Eric Staal, who’d go on to win a Stanley Cup and Olympic gold, building a borderline case for the HHOF, but the fall-off was dramatic after that. The Canadians never had a sniff at the medal round and were rag-dolled by the U.S. 10-3.

(7) Zherdev would wind up being selected by the Columbus Blue Jackets with the fourth overall pick in the 2003 draft, what is universally considered the richest, deepest draft class in league history. At the draft Columbus GM Doug MacLean crowed that with the fourth overall pick he had landed the player he’d have selected at No. 1—yeah, he was dancing in the end zone. I was hugely skeptical of that and made a point of quizzing MacLean about Zherdev.

Zherdev’s rookie card is $1.29 on eBay

“Is Zherdev a good passer?” I asked.

“He’s a great passer, a great playmaker,” he replied.

“I’m not sure he’d pass you the salt,” I said. I noted that I had seen him play a dozen or so games between the under-18s and the under-20 tournament in Halifax and couldn’t remember him voluntarily giving up the puck. Maclean blew me off.

MacLean was still the GM of the Columbus Blue Jackets back in 2006, when he agreed to let me into management’s war-room in advance of the draft for an ESPN The Magazine feature. I’m sure MacLean green-lit my request because he thought it might score much-needed points with the owner, John H. McConnell, who must have grown tired of missing the playoffs in the Jackets’ first six seasons in the league. Exacerbating ownership’s frustrations was the relative success of the Minnesota Wild who came into the league at the same time as Columbus and made it all the way to the conference finals in the franchise’s third season. In that one run, the Wild won as many playoff rounds as the Blue Jackets have in their first 24 seasons.

I wound up developing the ESPN The Magazine feature into a book about the behind-the-scenes business at the draft, Future Greats and Heartbreaks. It should be noted that Maclean was fired at the end of the 2006-07 season. Upon his firing, MacLean said: “We've got an unbelievable foundation in place. I look around the league and how many teams would I trade ours for? Not many."

Delusional, really. The Blue Jackets didn’t completely botch the picks in the two seasons I spent around the organization (Derek Brassard in 2006, Jakub Voracek in ‘07, though the latter was after MacLean’s firing), but Zherdev in a draft that was rife with future HHOF—MacLean’s and presumably the Jackets’ top-ranked—is a gaffe for the ages. That MacLean later wrote a book about the draft process is beyond satire—I should pick it up just see how he explains the wisdom of taking a left winger out of the Quebec league, Alexandre Picard with the eighth-overall pick in 2004 (career totals of zero goals, two assists in 67 games across five seasons).

Picard’s rookie card is available eBay for $1.95 (or best offer)

Picard’s disappointment couldn’t be ascribed to injury—he’s still playing in the Quebec senior league in Chicoutimi.

(8) Ovechkin’s name also had a funky misspelling on scoresheets from the under-17 tournament months before, as noted in this SubStack’s entry No. 255.

(9) Patrick O’Sullivan was the youngest frontline player on the U.S. team and a force himself in the tournament. My first piece for ESPN The Magazine in May 2003 was a profile of Patrick who endured and overcame a history of physical and emotional abuse that wound up landing his father in jail. I later helped Patrick write Breaking Away, a best-selling memoir.

OKAY, so the footnotes are longer (and more fun) than the text. All in the SubStack spirit.

Tomorrow, I’ll lay out how agents battled to represent Ovechkin, but to give you an idea of the landscape, I’ll refer you to that aforementioned piece from June 2002. Those who tried to describe the business of representing Russian prospects in that era usually opted for one motif: the Wild West.

FEEDING THE NEW RUSSIAN REVOLUTION:

The cut-throat deals that fuel the NHL's entry draft

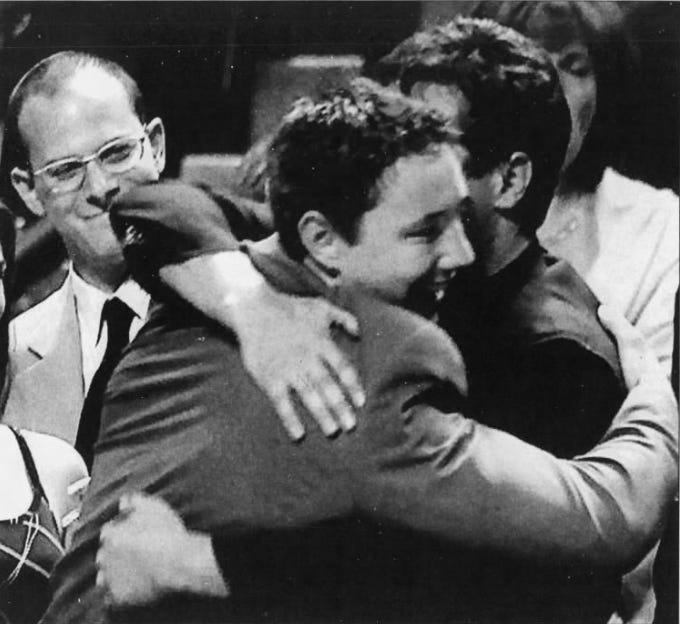

Jay Grossman (left) beams as his client Ilya Kovalchuk accepts congratulations having been selected the first overall pick in the 2001 NHL entry draft.

On a Thursday afternoon last June a dozen future millionaires mingled in a crowded bistro in Fort Lauderdale. They were easy to spot. They were the ones wearing hockey sweaters, the ones being interrogated by sportwriters and the only ones not old enough to drink.

Every year on the eve of its entry draft the National Hockey League introduces the world's top 18-year-old players to those who will cover their heroics for years to come, a coming-out party of sorts. It's a scene that will play out next week in Toronto before the draft on June 22, but last year the spotlight shone on a dark-haired prodigy in a Moscow Spartak sweater, Ilya Kovalchuk, who a year before had known little about the NHL and still seemed bewildered by the hoopla. In the final years of his junior career, Kovalchuk, a native of Tver, Russia, had courted controversy by shamelessly show-boating in international tournaments and cockily mocking rival juniors in the press. Nevertheless, NHL executives and scouts considered him the most exciting teenage talent since Mario Lemieux almost 20 years before, questions about his character be damned.

Kovalchuk is looking to Vadim Azrilyant (white ballcap) for direction while taking questions from reporters. That’s my friend John Wawrow from Buffalo right behind Kovalchuk and Montreal’s Pat Hickey bent over to prove to the crew that he still needs to part his hair. And yeah, I tool this photo with my trusty point-and-shoot Leica.

It should have been good news for the NHL. After all, the draft sells hope to teams on hard times. Kovalchuk was 6-feet-2-inches and 210 pounds of hope for the Atlanta Thrashers, Ted Turner's struggling expansion franchise and holders of the first pick in the draft.

It wasn't good news for Scott Greenspun of Impact Sports Management, a tiny boutique sports agency based in New York City. Anything but. Greenspun looked at Kovalchuk, saw only lost opportunity, one that would have netted him millions of dollars. Greenspun had once believed he had locked up Kovalchuk as a client. Now, he shrugged it off with a world-weary fatalism. "We're a small agency," Greenspun said. "We had an agreement with him going back a year before. His leaving us was a disappointment but not a surprise. We saw it coming."

Kovalchuk had dumped Greenspun for Jay Grossman, becoming another in a parade of top Russian teenage stars who had stiffed their agents to hook up with Grossman's SFX Hockey agency in New York.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.