No. 236: HORSE-RACE JOURNALISM / It's not just politics--it's sometimes horses. What the media that covers elections can learn about handicapping from racetrack veterans.

Featuring Secretariat. screenwriter William Goldman, John Jeremiah Sullivan and his sportswriter father,

Secretariat at the Belmont, with Ron Turcotte looking back on the distanced field.

WITH every election, you can count on one staple of all media platforms: horse-race journalism, handicapping races as if the candidates were thoroughbreds and standardbreds at the track.

For those who don’t know the term and for those who do and just want to grind their teeth some more, Annie Aguiar laid out a pithy definition of the horse-race journalism on the Poynter Institute’s website last summer.

Horse-race journalism is an old-school term for political reporting that treats minor updates in polling and campaign strategy like play-by-play announcer calls. The approach is criticized for a disproportionate focus on the odds of an election over the actual stakes.

The Poynter story is linked here, and it neatly sums up criticism of this approach to election coverage—horse-race journalism is candy served up to give a sugar rush to readers, listeners and viewers. By contrast, the stuff that’s good for you, the deep dives on issues that would inform voters, are broccoli or some other little loved vegetable. The audience loves horse-race journalism, but it does little or nothing that advances the public interest.

A U.S. election is the ultimate in horse-race journalism and seas of ink, tonnes of newsprint, whole days over the airwaves and great swaths of bandwidth were given over to handicapping the 2024 Trump-Harris match race (Joe Biden being a late scratch) and much less to policy and analysis, something that requires reporting, shoe leather and unglamourous toil.

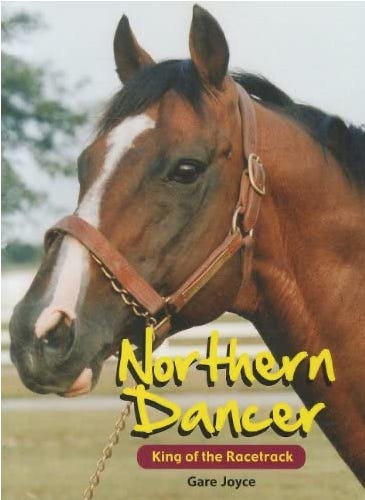

(A personal digression: I’ll never claim to be a horse-racing journalist, though one of the early books in my sorry-assed publishing career was about a champion thoroughbred. Yeah, hard at it is to believe, but I wrote this kids’ book about the only non-human in the publishing house’s kid-book series of Canadian historical biographies: Northern Dancer: King of the Racetrack. If you think you’ve got a difficult write-around, try laying out breeding for a 10- to 12-year-old reader)

In the Poynter piece, Joe Drape, a New York Times lifer at the racetrack, channels William Goldman, the great screenwriter (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men) and novelist (Marathon Man). Goldman famously said of producers and studios judging the potential success of movies in development: “Nobody knows anything.” Drape’s advice to those journalists who fancy themselves political handicappers is the same sentiment in the railbird vernacular.

“My colleagues who I admire in politics should remember that the rule of thumb in horse racing is, ‘Nobody knows nothing,’ You got opinions, you got information in front of you, you got speculation, but until the race is run, nobody knows who’s gonna win.”

Drape points out that his business isn’t just touting—there’s some stuff that’s predictive, but there’s also covering the races run and won and lost. The former is done and dusted at the finish line; the best of the latter can live forever.

“You drink mint juleps, you watch a two-minute race, you got 45 minutes to have an epic in miniature,” Drape says. “Horse-race journalism for politics is, ‘Who’s up? Who’s down? Who looks good going into the first turn? Who looks good down the backstretch? Who’s closing quick?’ They’re putting the lexicon of horse racing onto political campaigns.”

“You watch a two-minute race, you got 45 minutes to have an epic in miniature”: God, I love that.

When Drape references “mint juleps,” he’s drawing on traditions and practices at the Kentucky Derby, the horse race with the richest of traditions. (Sincere apologies to Epsom Derby, sorry Grand National.) The record for the Derby is held by Secretariat, the wonder horse that ran the first sub-two-minute mile-and-a-quarter in the first of the jewels in the Triple Crown.

As a goofy exercise, I went back to look at what the horse-race journalists were saying in advance of Secretariat’s breakthrough moment. Six weeks after the 1973 Kentucky Derby, capping the Triple Crown with a 30-length victory at the Belmont Stakes, Secretariat was the greatest thoroughbred that had ever set a hoof on a track, so the scribes declared. They’d try in vain to come up with equivalent performances in any sports that matched the wonder horse’s.

On the eve of the biggest race won in stunning fashion by the greatest of champions, who had the scribes projected as the winner in the days before? Maybe political horse-race journalists can draw lessons here or, in the wake of so many apple carts getting knocked over Tuesday night, find some consolation.

Oh, and along the way, I’ll dive into a piece of horse-racing journalism of an entirely different sort: Blood Horses, by John Jeremiah Sullivan, the life story of a scribe who covered the 1973 Derby, as movingly told by his son.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.