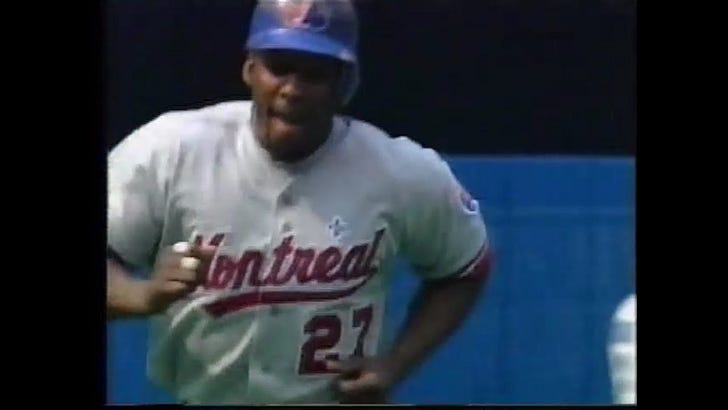

No. 228: FRANK ROBINSON / The Expos were slated to be scrapped & wouldn't have taken the field in '02 if Bud Selig had his druthers. He tapped a HOFer to manage the Expos for the zombie season.

A loyal lieutenant to the Commish, Robinson told me that the unenviable assignment was "the perfect job." Later he'd be talked out of resigning.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.