No. 166: GOLD-MEDAL CHEAT / Ben Johnson got nabbed, but Waldemar Cierpinski has two Olympic golds that aren't rightfully his.

We tracked the leaders of the Olympic marathon in Montreal in '76. While Cierpinski passed the drug test like the other East Germans, we thought he didn't pass the eye test. He couldn't win that easy.

I’VE written in this space about my boyhood love of track and field. Not so long ago, I wrote about my cross-country and track coach at East York Collegiate. Check out the story linked here. No. 153: RON HUNGERFORD / In a "Sweetness and Light Edition" of How to Succeed in Sportswriting, the story of a high-school coach who dedicated his career to helping others to succeed.

I also wrote about a very unlikely meeting with one of my boyhood track and field heroes, a man on any short list of the greatest middle distance runners of all time. Check out No. 144: PETER SNELL / The greatest athlete I ever talked to, a three-time Olympic gold medalist, took refuge in his anonymity.

Both of these are recent entries so you won’t need a paid subscription to access them. For stories going back more than two months, you will need access, so here’s a brief commercial word.

Back in the late July of 1976, when I was 19 and had barely escaped Grade 13 on a second try, I managed to weasel out of a couple of shifts at the Coca-Cola plant and drive up to Montreal with my buddy Gus, who later become a Mountie in B.C.. We had scored tickets to the second last day of the track and field competition at the still roofless and never-to-be-truly-finished Olympic Stadium.

We had premium seats—I believe they were the then astronomical sum of $32 but Gus and I were distressed to find TV cameras perched in our seats—had we been scammed. No, just dumb luck. When we asked ushers what our options were I feared the worst, namely that we’d be up in standing room in an upper deck or something. Instead, they moved us to an area designated for VIPs and coaches and such, just ten rows up from the finish line, seated beside a bunch of Finnish officials.

As it was late in the schedule the day wasn’t short of highlights—yup, we got to see the second day of the decathlon which was won by the Athlete Formerly Known as Bruce Jenner. No one had any idea how that story was going to turn out—the Wheaties box, guest shots on TV action shows, a commentator’s spot … but who knew?

Great day for the Finns that we were seated with, as they’d witness one of their nation’s greatest Olympic moments: Lasse Viren’s run to the gold in 5,000 metres, which gave him a sweep of the 5k and 10k in consecutive Olympics. I dug this up: the souvenir program featuring Viren running ahead of an unnamed Canadian on the cover, that I bought that day.

Gus and I stuck around for Saturday (driving an hour outside Montreal to camp because all rooms at the inn were gone and out of our price range anyway). We didn’t have tickets or any real chance of scoring them. God, We had tried to rustle up tix to get into the Forum for boxing where Sugar Ray Leonard and the Spinks brothers and Teofilo Stevenson were lighting it up in the finals. No dice. Just being on the streets in Montreal was enough on Saturday though, because that was where the marathon was being run. (No need to say the men’s marathon, because the women’s event wouldn’t be added until 1984.)

The Olympics has had its share of scandals and cheating has been in the mix many times. We knew enough about track to know that there had been questions about Lasse Viren and blood doping—transfusions of oxygen-rich blood ahead of competition. We also knew that a lot of athletes in the weight events or sprints wereon steroids programs—shit, there were guys on our high-school football team using them. The marathon, though, even with the suspicions about Viren, that figured to be a cleaner competition.

Hey I was 19, asking Globe and Mail columnist Dick Beddoes to autograph a napkin, so what did I know? (See No. 14: DICK BEDDOES / I'm not apologizing for my boyhood sportswriting hero, just empathizing for a broken guy. (You’ll need a subscription to access this early entry.)

The race was hugely disappointing. Viren faded, no surprised. Jerome Drayton, the Canadian world-ranked No. 1 in the marathon in the mid-70s, picked an awful time to come down with a cold. Frank Shorter fell short of winning in consecutive Olympics. And worst of all, a no-name won.

Turned out Gus and I were witnessing a dirty marathon.

I originally reported and wrote this piece about the 1976 Olympic marathon for espn.com back in August of 2008. I’ve tweaked the text a bit—edits that clean up the timeline somewhat. I’ve punched in a few memoir-ish lines about watching the race on the streets of Montreal, so it’s not the espn.com piece. That said, the reporting around the issue stands. In the 15 years since publication, nothing has changed, The principals in the race mentioned here are still with us, older, greyer and in the case of Cierpinksi, the mystery man or villain of the piece, balder.

Joking jabs aside, neither the IOC or the IAAF or other international sports federations have made any real attempt to right wrongs—there’s been no stripping of medals from steroid cheats, no voiding the records they set. Cierpinski still has his gold medals from Montreal in ‘76 and Moscow in ‘80 and the likelihood that the IOC will step in grows less likely with every passing year since East Germany’s Stasi files were opened in the early 90s. The GDR’s Marita Koch still has her record in the 400 metres of 47.60 set at the worlds in 1985—since she set the mark, no one has come within half second of her mark and only five women have run sub-49. Some East German Olympians have talked about their use of banned substances and Stasi connections, but to this point Cierpinksi and Koch and the other headliners have been silent. You can hold out hope for deathbed confessions if you like.

From espn.com

Thirty-two years ago, I was lucky enough to witness a bit of Olympic history. Some friends and I scored tickets to a few events at the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal. And we were just outside Olympic Stadium, on a downhill stretch, to watch the last mile of the men's marathon.

The marathon is one of the most prominent Olympic events. There really isn't a forgettable one. In 1976, even though African nations boycotted the Montreal Games because of the New Zealand national rugby team's tour of South Africa, the men's marathon had many outstanding runners and famous names. The field included: Frank Shorter, the favorite, who had won the 1972 Olympic marathon in Munich (the first American to win the gold in that event since Johnny Hayes in 1908); Bill Rodgers, who had won the Boston and New York City Marathons in 1975; and Finland's Lasse Viren, the mystery man, who had won the 5,000 and 10,000 meters in Munich and Montreal, and was running the first marathon of his career.

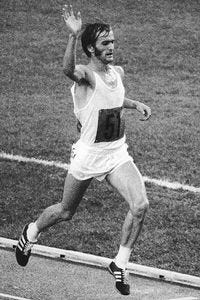

Waldemar Cierpinski waves on his way to Olympic gold in Montreal.

The conditions were poor for the runners, and maybe worse for the spectators, thanks to a steady drizzle all day long. When we finally saw the first runner approach the stadium -- a balding guy, clad all in white, we didn't recognize him. In fact, even the top contenders didn't know who he was. "All race long, I thought it was Carlos Lopes, the Portuguese runner who won the silver in the 10,000," Shorter said.

As it turned out, it was Waldemar Cierpinski, an East German who had competed internationally in the steeplechase, but had no record as a marathoner. But you'd never have known that, the way he pushed the pace that day. He looked less tired than we did on the sidewalk.

Shorter was the next runner to come into view, followed by Karel Lismont, the Belgian who had won the silver medal in the marathon in 1972. Lismont was only a few meters ahead of another American runner, Don Kardong. Then came Viren. Rodgers had dropped behind the lead pack. So had everyone else.

When the lead runners reached the stadium, the order didn't change. There were no late passes. Kardong was closing in on Lismont for the bronze, but he fell just a few strides short. And Cierpinski's win didn't look like a fluke. He won going away. In fact, he even ran a full extra lap inside the stadium at full throttle, unsure of where the finish line was.

It was an upset for the ages. And those who crossed the line behind Cierpinski couldn't grouse about it. The best man clearly had won. In general, track and field is unambiguous. Nothing is left in the hands of judges. There are no questionable calls. It's all about times, heights and distances.

At least it was for 20 years.

Everything changed in the mid-1990s, a few years after the Berlin Wall was knocked down and the German Democratic Republic was no more. That's when the GDR's archives were opened up, and the secrets of East Germany's success in Olympic sports were revealed. Long-standing suspicions were confirmed.

My friends and I had seen history on that marathon course in Montreal. Everyone suspected that steroids were a stain on other events, like the sprints, the throws and the rest. But it seemed like the marathon was above it all. It wasn't. We'd seen the first dirty Olympic marathon.

Was it the first? Even in London in 1908, there was talk that the marathon wasn't on the up-and-up. Canadian Tom Longboat, a Boston Marathon record-holder and a prerace favorite, was in second place when he dropped out after 19 miles, suspecting that he'd been poisoned by either rival coaches or gamblers. But nothing was ever proven.

Back in 1976, some people might have bet that the marathon wasn't going to be clean. But it wasn't Cierpinski they were talking about. Lasse Viren's success had led some to believe he had been blood doping -- getting transfusions of red blood cells. Viren admitted to drinking reindeer milk, but he owned up to nothing else.

There was no testing for blood doping back in '76, but there was steroid testing. In fact, the Montreal Games were the first Olympics to have steroid testing. The testers did manage to catch one cheat in track and field: Poland's Danuta Rosani-Gwardecka, who finished 14th in the women's discus. But according to the test results, every other track-and-field event, including the men's marathon, was clean.

The 1976 Games were also the breakthrough Games for East Germany. The GDR had a population of 16 million people, but came away with a whopping 40 gold medals in Montreal, second only to the Soviet Union's 49 and ahead of the United States' total. The rest of the world had suspicions about the East Germans, but most focused on its female swimmers, who won 11 out of 13 races and looked like the Butkus sisters. Suspicions were also focused on its women's track team, which won nine of 14 events. But not on the marathon champion, Cierpinski, though.

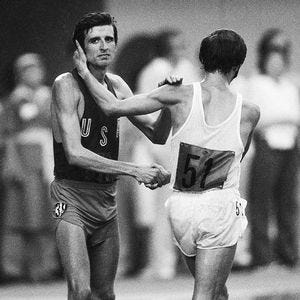

Cierpinski and Shorter embraced when the race was over.

Those left in Cierpinski's wake were stunned by his performance. "He had 100 meters on me, but late in the race I closed to within 50," Shorter said. "He looked back and accelerated and made it look easy. It was so unusual. I'd never seen anything like it in all my races before."

Still, Shorter said, he didn't give a single thought to Cierpinksi using performance-enhancing drugs. "In the heat of the event you're focused on what you're doing," he said.

Four years later, Cierpinski went on to win the Olympic marathon again in Moscow. In 1983 he finished third in the marathon at the inaugural World Track and Field Championships in Helsinki. That was his last major marathon. The Soviet-led boycott of the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles denied him a shot at a third consecutive Olympic marathon gold. Still, Abebe Bikila of Ethopia was the only other runner to win two Olympic golds in track's longest test. Cierpinski's legacy looked to be secure.

Things changed in 1998, when a German scientist, Dr. Werner Franke, managed to get into the archives of Stasi, East Germany's secret police force. By the time the GDR collapsed, Stasi's spooks had managed to destroy most of its incriminating paperwork, but not a file on State Plan 14:25, which Dr. Franke uncovered at the Stasi headquarters in Leipzig. State Plan 14:25 contained details of East Germany's drug program for its Olympic athletes. The file implicated many gold medalists, five of them winners in track and field in Montreal. Cierpinski's name was at the top of Page 105. He was No. 62.

"The documentary evidence is there," Shorter said. "I'm convinced Franke knows something [more]."

It seemed incriminating enough for the International Olympic Committee to follow up with an inquiry -- maybe even a commission that could reopen the record book and reassign medals? But, no such luck.

When the documents first came to light in 1998, then-International Olympic Committee president Juan Antonio Samaranch declared that there would be "no rewriting history." The results from the 1976 Summer Olympics look like a dead issue now -- even though U.S. Olympic relay runners recently had to hand back medals from the 2000 Games in Sydney because team members Antonio Pettigrew and Marion Jones were exposed as steroid users.

It might end up being the only Olympic marathon that I'll ever see in person, and it was a lie. If I feel cheated, how do those who were actually in the race feel?

When Dr. Franke first revealed State Plan 14:25 to the world, the press made it seem like Shorter was on a mission to scrub Cierpinski's name and other East Germans from the record books. "As someone potentially harmed by this [East German doping], under German law I have the right to the documents," Shorter told the Rocky Mountain News in 1998. "How much persistence are [former] Olympic athletes going to have in this process? You're dealing with a very persistent pool of people."

If anyone felt cheated, though, you'd assume it would be Don Kardong. If Cierpinski's win were voided, Kardong would move up from fourth place to the bronze medal. Back in 1998, though, Kardong sounded philosophical about it. "In the purest sense, the judgment of the IOC is irrelevant," Kardong wrote in Runner's World magazine 10 years ago. "It is the athlete's own measure of self that matters. In my moment of truth, I lost the bronze medal to Karel Lismont. I reached down and found … a well of fatigue. I can't change that, but at least I can claim my race -- what I did and didn't do -- as my own."

But things change. At least, some things change.

These days Shorter wants to make it clear that he wasn't just out to upgrade his silver from Montreal to a gold. He was seeking justice and fairness, more than any personal or selfish ends. "I never actively campaigned to have the results from '76 changed," Shorter said. "I can feel good about what I have done in my running career."

Left to right: Shorter, Cierpinski, Lismont

Like he did on the streets of Munich and Montreal, Shorter was looking ahead, not behind him. A lawyer in Boulder, Colo., he took a lead role in the founding of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency in 2000, and served as its chairman until 2003. "If the IOC had ever pursued an inquiry [about Cierpinski] I would have had to recuse myself," he said.

Shorter is convinced that the IOC is on the right track -- a lot of distance has been covered, going from Samaranch's belief that results should be etched in stone to the disqualification of cheaters from the 2000 Olympics eight years after the fact. "I have to give [current IOC president] Jacques Rogge credit," he says. "Rogge has done as good a job as anyone on the planet could do. A lot of progress has been made."

Meanwhile, Kardong sounds a little less accepting of the results from Montreal than he did when Dr. Franke first went public with State Plan 14:25.

"The IOC should do something to acknowledge the fact that the East Germans were cheating," says Kardong, who has long been the chief organizer of the Bloomsday Run in his hometown of Spokane, Wash. "I don't know if the IOC should make some sort of statement, or have something in the record books. I don't know how feasible it is to go back and start changing the order of finishes in all those events. It's an incredibly complicated issue. It's hard to know which East German athletes knew about the drugs they were being given, or if they had any choice even if they knew. Some were victims of the system and had to sacrifice their health and even their lives.

"There's only one thing that would be wrong, and that is to do nothing, which is what the IOC has chosen."

Some things don't change, though.

What Cierpinski thinks about the race in 1976 and State Plan 14:25 is still a mystery. He has declined all interview requests over the years. "If I were his lawyer, I'd give him the same advice," Shorter said. "Say nothing."

Cierpinski's name is still in the record book. So are the names of a bunch of the GDR's Olympic champions whose names show up beside numbers in Stasi documents.

As it stands now, the IOC has a statute of limitations on its chase of drug cheaters: eight years. Montreal is 32 years ago and counting. But if ever history has needed to be rewritten, the time is now.

An asterisk? A footnote? Declaring all GDR results null and void? It will never change what Shorter saw when Cierpinski pulled away from him, what Kardong saw when Lismont beat him to the tape for third place, what we saw on the streets of Montreal. But it would change how we look at the Olympics, an event that would still have stopwatches, but no time limits on fairness.

Thanks for reading. Here’s a German-language look at Cierpinski. I’d be interested if anyone can do a translation for me. And, yeah, I did look for myself on the sidewalks in the video from the Montreal race.

And below the paywall for my faithful paid subscribers I’ve dropped in a feature that I wrote in 1998 about Canadian Olympians who seemed very forgiving and even sympathetic to East German athletes who had bested them for medals in Olympics in the 70s. Cierpinski and Don Kardong makes something more than cameo appearances.

Coming clean in drug scandal Olympians have differing views whether cheaters should be purged from record books

The Globe and Mail

July 25 1998

IT was never just suspicion. The athletes all knew that the East Germans were on steroids. All the others on the starting line knew the ones in the dull blue singlets were cheats. And now, more than 20 years after the cheering, some athletes worldwide are looking on with interest as German courts address the second-hardest part: proving it.

On trial in unified Germany are the sports organizers of the former East Germany. The number of people charged could eventually total 700 and involve more than 1,000 cases of doping.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall, intelligence files were opened throughout Eastern Europe. East German files reveal that its national teams, forces at almost every Olympic venue, were steroid-boosted Stasi operatives. The world knew they were cheats, but might have been surprised to find out that many were spies to boot.

Still, the scientific and legal issues are all just the second-hardest part. The hardest: What to do when all that they knew becomes a matter of record? What had been sport became chemistry and then history. Now all that remains are ethical dilemmas: How do you hold accountable the mighty sports machine of a nation that has ceased to exist? What do you do with the medals and the records?

Some famous names have come forward to submit that they were cheated. The best-known case centres on the marathon at the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal. The defending champion, Frank Shorter of the United States, finished second, upset by an unheralded East German steeplechaser, Waldemar Cierpinski. Cierpinski had Shorter's number in '76, but in 1998, Shorter has No. 62, Cierpinski's number in the file on State Plan 14.25, the East German team's doping program.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to How to Succeed in Sportswriting (without Really Trying) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.