No. 17: THE CREE NATION (EEYOU) / Behind the scenes on my stories from Waswanipi

Inevitably you find stories going for other stories

I’m taking some pride in this story in The Athletic on Wednesday. I’m also taking some relief when it landed on the website. Here’s the link to the finished product.

You might find it behind a paywall but I’ll explain the drift for those who aren’t subscribers to the site. More to the point I’ll explain the genesis of the story.

The drift of the story: Like many and probably most Cree kids in northern Quebec for many decades Doug Happyjack was taken from his family at age six and shipped to a residential school. In Doug’s case, the residential school was in La Tuque, Quebec, hundreds of miles from his parents. And in Doug’s case, the unconscionable residential-school system in the province was in its death spiral and would shut down for good in 1978, when he was 12. In his last year in La Tuque, he played for the school’s peewee hockey team that was coached by a tyrannical and predatory Anglican priest who emotionally, physically and sexually abused the boys. After a lifetime of trauma and after witnessing the devastating effects of the trauma on teammates and other survivors of the residential-school system, Doug opened up for the first time about his experiences. He never testified at the Truth and Reconciliation hearings years back, never sought any special compensation for damages wrought by the church- and government-sanctioned school. He never even told his wife and children. His only motivation for talking to them and later to me was to heal.

That’s the story in a nutshell. If you’re going to read only one story of mine, read this one. Not as a favour for me, but rather for Doug and others who paid such an awful price. There’s really no comprehending the damage that has been done by the residential-school system and there’s no undoing or fixing or righting it—stuff I tried to touch on, but let’s face it, no single story can fully frame it.

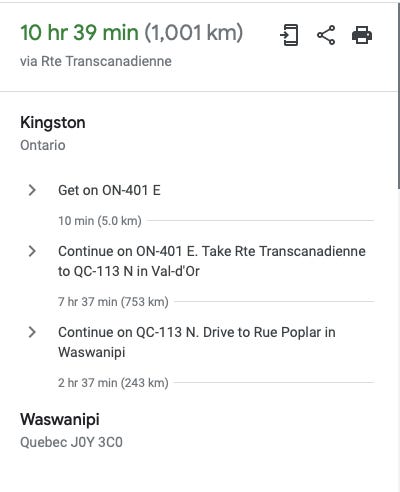

Now to the genesis: I’ll try to keep it shorter than the ten hours I drove north of Ottawa in blizzard conditions dodging moose and road-hogging lumber trucks to get to Waswanipi for five days last December.

Back in September 2021, on a trip to Quebec City, I visited with Patrick Dom, the head man of the Quebec International Peewee Tournament. I had first met Patrick when I was writing a story about two teams heading to the 2012 tournament: Little Caesars, a powerhouse program out of Detroit; and a bunch of over-achieving kids out of Yorkton, Saskatchewan, by far the smallest community represented in the tournament. A study in contrasts, a gift to write: Here’s the story that came out of it for Sportsnet Magazine. (It’s probably not legible on your phone, but on a laptop you should be able to make it out.) Amazingly the two kids I focused on, good players but neither the No. 1 stars of their team, both made it into the CHL: Yorton’s Alec Zawatsky in the Dub with Saskatoon, Swift Current and Moose Jaw; and Little Caesars D.J. (Buzzy) Busdeker with Saginaw. Alec was coached by his father, an ex-pro in the German league and, as a leader of boys and men, a step up from his son’s coach at the University of Saskatchewan last winter, Mike Babcock.

When I asked Patrick Dom last September if he had any teams of interest landing in the 2022 tournament, any handicapping required a leap of faith. The 2021 tournament was cancelled due to COVID-19 and even when we were sitting in his office we were wearing masks. The event is enough of a logistical nightmare in a good year—Patrick was trying to figure how to do a 120-team international tournament bringing in teams from around the world with vaccination requirements snagging travels and billeting, the usual key to player accommodation, out of the question because of the pandemic. Dom and his staff were operating on the assumption that they would have an event of some sort, though exactly what it would look like no one could hazard a guess.

I asked Patrick if there were any teams of interest who were going to be in the field for the (fingers crossed) 2022 tournament and he mentioned the Cree Nation Bears, a select team drawn from the James Bay Minor Hockey League. Playing out of Waswanipi, the Bears are the only all-Indigenous program fully federated under the auspices of Hockey Quebec. When they head out on the road in the Abitibi-Temiscamingue league, they travel to play non-indigenous teams in Amos and Rouyn-Noranda, which are at least three and four hours away in good weather. The International tournament tries to draw at least one team from each of the regional leagues approved by Hockey Quebec, but only a few have made it down from Abitibi-Temiscamingue. “We’re really trying to get the Bears in the tournament,” Patrick told me.

Organizers usually have the field set in August, but as noted, this was the farthest thing from a usual season. Only in late November did Patrick confirm that the Bears were in. I made a couple of phone calls and sent a couple of emails and off to Waswanipi I went.

The directions (above) do not account for snow ploughs moving 20k an hour.

On the drive, while watching out for moose, dodging logging trucks and braving blizzard conditions, I had a conversation on the speaker phone with a semi-retired sportswriter (younger than me). When I explained my destination and my story my friend was puzzled.

“You still want to do that stuff?”

Yeah, in my supposed dotage, I do. I wound up on the road for eight days, staying six nights in Waswanipi in a band-owned mobile home usually reserved for workers coming from outside Cree territory. The nearest hotel was three hours away and the shortness of the days and danger of night driving just made staying off-site unworkable. Ditto the nearest restaurant. There was a gas-station convenience store by the highway but with limited stock, a byproduct of COVID travel restrictions laid down by the band. A few workers for the band made trips into Chibougamau for supplies on weekends and most folks had a lot of game in their freezers, whether it was moose or goose or whatever. As almost certainly the only non-meat-eater in Waswanipi, I was living on peanut butter on crackers and ramen noodles. But yeah, I still want to do this stuff.

The story seemed star-crossed from the get-go: two weeks after I visited Waswanipi, with the players home for the holiday break, the team’s season was suspended and likewise the Quebec tournament because of the spike in COVID numbers. That both would be improbably salvaged in the spring wound up becoming my story for Sportsnet.ca.

(Above) The illustrations for the Cree Nation Bears story were the work of Kyle Charles, an Edmonton-based Cree artist whose work has appeared in DC and Marvel publications.

While I was in Waswanipi I met the chief of the band, Marcel Happyjack. After I thanked him for finding me a place to stay and extending me undeserved kindness throughout my stay, I laid out the story I had come north to write: the Bears’ trip to the Quebec tournament. Marcel told me that I should give his brother Doug a call. Doug, he told me, had played in the Quebec tournament. Only when I spoke to Doug did I realize that his story was much more. And only by making the trip to Waswanipi would I have met the Happyjacks.

I’d love to say that I dug this story up but really by landing in a place so far off the usual sportswriting axis did I happen on an important story.

The object lessons:

One: Sometimes you have to get lost to find something.

Two: The only way you earn trust is showing up, even if it means going an extra 600 miles.

I want to thank Evan Rosser, my editor at Sportsnet, for supporting me on the Cree Nation piece and for likewise suffering all the twists and turns that I put him through for years, every too-long draft, every goofy idea.

I also want to thank three folks at The Athletic: chief content officer Paul Fichtenbaum for listening to my pitch on the La Tuque residential school; senior managing editor for enterprise and investigations George Dohrmann for likewise getting it; and NHL enterprise editor Mark Wollemann for letting me get lost in my first draft before I could find the story on my next swing.